- HOME PAGE

- WELCOME TO BMA

- HIPAA AND PRIVACY PRACTICES

- "MYCHART" health portal

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- After Hours Emergency Calls

- PCP, NP and PA Profiles

- Our Specialists and Specialty Services

- MT AUBURN DIABETES CENTER

- ABOUT OUR OFFICE

- Being Our Patient

- REFERRALS : online request form

- Patient LIBRARY

- Turning 65? MEDICARE explained

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- FIVE WISHES AND HEALTHCARE PROXY

- Social Work Care Coordination

- Quality Care Measures

- MACIPA

- BULLETIN BOARD

- In Memoriam

- Job opportunities

MENTAL HEALTH THERAPY

Suite 5300

725 Concord Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138

617-802-6522

Dr Nicole Coconcea

Help Wanted: a Good Therapist

Amid Increasing Choices, How to Know What Treatments Work, When to Move On

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : October 15, 2011

Therese Borchard likens herself to Goldilocks of the mental-health world: She tried six psychiatrists before she found one that was "just right." One learned she was a writer and asked for help with a book proposal. Another put her on sleeping pills, ignoring her history of substance abuse. One even wanted to try hypnotic regression by candlelight to address unresolved childhood issues.

Finally, No. 7 diagnosed bipolar disorder, found medication that was effective, helped her to be less hard on herself and "salvaged the last crumb of my self-esteem," says Ms. Borchard, who writes the popular "Beyond Blue" blog on Beliefnet.com.

The search for the right therapist can be baffling—and it comes at a time when would-be patients are feeling most vulnerable.

Patients who aren't sure what's wrong with them can be stumped about the type of therapist to call and ill-equipped to evaluate what they're told during treatment. How well a therapist's personal style matches a patient's individual needs can be critical. But experts also say that patients shouldn't be shy about pressing their therapist for a diagnosis and setting measurable goals.

David Palmiter, a public-education coordinator for the American Psychological Association (APA), likens good therapy to going to a good restaurant: "You should be able to peer into the kitchen and see what they're doing."

About 3% of Americans had outpatient psychotherapy in 2007—roughly the same as in 1998—although the percentage taking antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs rose sharply, according to an analysis in the American Journal of Psychiatry last year. The same study found that the average number of visits dropped from nearly 10 in 1998 to eight in 2007.

By some estimates, one-quarter of the U.S. population has some kind of diagnosable mental illness. But many don't believe they need help, don't know how to get it, think they can't afford it or that it won't be effective. There's also the lingering stigma attached to seeing a "shrink."

Approaches

There are many types of therapy, including:

Numerous clinical trials have shown that various forms of psychotherapy, with or without medication, can help ease depression, anxiety and other disorders. One oft-quoted analysis of 2,400 patients found that 50% improved measurably after eight sessions, and 75% improved after six months in therapy. Still, that doesn't mean that any given therapist will be effective for any particular patient.

One issue for prospective patients is that therapists generally specialize in one treatment approach and tend to see patients' problems through that lens. A cognitive-behavioral therapist will focus on changing patients' negative thinking patterns, while a psychoanalyst will want to probe more deeply into how the past is affecting current issues.

Some clinics and university mental-health centers offer consultations to help evaluate which treatment might be best. "Patients shouldn't have to decide this by themselves," says Drew Ramsey, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at New York's Columbia University, who says he loves to play "shrink matchmaker."

Patients can also ask friends, family members and physicians for referrals, then call several recommended therapists themselves and ask about their experience and techniques. "You may not know what kind of approach is right, but you can say, 'Here's what's going on in my life. How would you propose treating that? And how long do you think it would take?' " says Lynn Bufka, assistant executive director for practice research and policy at the APA. Increasingly, therapists are measuring outcomes, such as asking patients for evaluations, she adds. "So it's very reasonable to ask, 'How do you know what you do works?' "

Once in treatment, both the therapist and the patient should be familiar enough with each other by the third session to know if it's a good fit, experts say.

"Some people need a therapist who gives them instructions and assignments, and some people hate that. Some people need a therapist who is basically silent and lets them talk," says Betsy Stone, a psychologist in Stamford, Conn.

Dr. Stone says she can often tell even in the first session if the fit isn't right. "I like to push patients pretty hard, because I want them to get their money's worth, and some people are just too fragile," she says. "Then I say, 'I'm not the right therapist for you, but I'll help you find someone else.' "

Increasingly, therapists are collaborating with patients on a treatment plan rather than remaining aloof and omniscient. "I encourage patients to look up the science for themselves. How can they do that if they don't know what terms to search for?" says Dr. Palmiter.

Effective therapy can be difficult at times—particularly when the patient is exploring painful thoughts or fears. "A good therapist should give you comfort and discomfort at the same time. They should make you feel understood but challenged," says Dr. Stone.

Distinguishing that from having an uncomfortable relationship with the therapist can be tricky. "If you leave therapy every week feeling worse than when you went in," says Dr. Bufka, "it's probably not the right place for you."

Studies show that patients often hesitate to break it off because they don't want to hurt the therapist's feelings or seem ungrateful. "But believe me, we're used to it—and it's a very valuable thing to hear," says Dr. Palmiter.

Even close relationships sometimes fail to get at the right issues. Victoria Maxwell, 44, an actress and blogger from Half Moon Bay, British Columbia, says she worked with a therapist for 2½-years as a teenager and liked her enormously. But she never made much progress, because the therapist didn't recognize Ms. Maxwell's underlying bipolar disorder. "I became a really insightful depressed person. But it wasn't helping my depression," she says.

Years later, after several hospitalizations, a nurse referred Ms. Maxwell to an older psychiatrist. She initially thought they'd be a bad fit—but found he was the only one who believed she could have both a profound spiritual experience and bipolar disorder. "I trusted him, so I was willing to try what he suggested, which included medication," she says. "I wouldn't be where I am today without his help and understanding."

Setting measurable goals is crucial for knowing whether a therapy is working. In Ms. Maxwell's case, her psychiatrist said, "I think you're capable of moving out of your parents' home, living with roommates and driving a car—and I was," she says.

Amid Increasing Choices, How to Know What Treatments Work, When to Move On

By Melinda Beck : WSJ : October 15, 2011

Therese Borchard likens herself to Goldilocks of the mental-health world: She tried six psychiatrists before she found one that was "just right." One learned she was a writer and asked for help with a book proposal. Another put her on sleeping pills, ignoring her history of substance abuse. One even wanted to try hypnotic regression by candlelight to address unresolved childhood issues.

Finally, No. 7 diagnosed bipolar disorder, found medication that was effective, helped her to be less hard on herself and "salvaged the last crumb of my self-esteem," says Ms. Borchard, who writes the popular "Beyond Blue" blog on Beliefnet.com.

The search for the right therapist can be baffling—and it comes at a time when would-be patients are feeling most vulnerable.

Patients who aren't sure what's wrong with them can be stumped about the type of therapist to call and ill-equipped to evaluate what they're told during treatment. How well a therapist's personal style matches a patient's individual needs can be critical. But experts also say that patients shouldn't be shy about pressing their therapist for a diagnosis and setting measurable goals.

David Palmiter, a public-education coordinator for the American Psychological Association (APA), likens good therapy to going to a good restaurant: "You should be able to peer into the kitchen and see what they're doing."

About 3% of Americans had outpatient psychotherapy in 2007—roughly the same as in 1998—although the percentage taking antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs rose sharply, according to an analysis in the American Journal of Psychiatry last year. The same study found that the average number of visits dropped from nearly 10 in 1998 to eight in 2007.

By some estimates, one-quarter of the U.S. population has some kind of diagnosable mental illness. But many don't believe they need help, don't know how to get it, think they can't afford it or that it won't be effective. There's also the lingering stigma attached to seeing a "shrink."

Approaches

There are many types of therapy, including:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Identifies and changes harmful thinking patterns; may involve gradual exposure to whatever is causing fears.

- Interpersonal therapy. Explores how relationships involving grief, isolation, conflict or changing family roles contribute to psychological problems.

- Psychoanalysis. Emphasizes how the unconscious mind influences behavior and how the past affects the present.

Numerous clinical trials have shown that various forms of psychotherapy, with or without medication, can help ease depression, anxiety and other disorders. One oft-quoted analysis of 2,400 patients found that 50% improved measurably after eight sessions, and 75% improved after six months in therapy. Still, that doesn't mean that any given therapist will be effective for any particular patient.

One issue for prospective patients is that therapists generally specialize in one treatment approach and tend to see patients' problems through that lens. A cognitive-behavioral therapist will focus on changing patients' negative thinking patterns, while a psychoanalyst will want to probe more deeply into how the past is affecting current issues.

Some clinics and university mental-health centers offer consultations to help evaluate which treatment might be best. "Patients shouldn't have to decide this by themselves," says Drew Ramsey, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at New York's Columbia University, who says he loves to play "shrink matchmaker."

Patients can also ask friends, family members and physicians for referrals, then call several recommended therapists themselves and ask about their experience and techniques. "You may not know what kind of approach is right, but you can say, 'Here's what's going on in my life. How would you propose treating that? And how long do you think it would take?' " says Lynn Bufka, assistant executive director for practice research and policy at the APA. Increasingly, therapists are measuring outcomes, such as asking patients for evaluations, she adds. "So it's very reasonable to ask, 'How do you know what you do works?' "

Once in treatment, both the therapist and the patient should be familiar enough with each other by the third session to know if it's a good fit, experts say.

"Some people need a therapist who gives them instructions and assignments, and some people hate that. Some people need a therapist who is basically silent and lets them talk," says Betsy Stone, a psychologist in Stamford, Conn.

Dr. Stone says she can often tell even in the first session if the fit isn't right. "I like to push patients pretty hard, because I want them to get their money's worth, and some people are just too fragile," she says. "Then I say, 'I'm not the right therapist for you, but I'll help you find someone else.' "

Increasingly, therapists are collaborating with patients on a treatment plan rather than remaining aloof and omniscient. "I encourage patients to look up the science for themselves. How can they do that if they don't know what terms to search for?" says Dr. Palmiter.

Effective therapy can be difficult at times—particularly when the patient is exploring painful thoughts or fears. "A good therapist should give you comfort and discomfort at the same time. They should make you feel understood but challenged," says Dr. Stone.

Distinguishing that from having an uncomfortable relationship with the therapist can be tricky. "If you leave therapy every week feeling worse than when you went in," says Dr. Bufka, "it's probably not the right place for you."

Studies show that patients often hesitate to break it off because they don't want to hurt the therapist's feelings or seem ungrateful. "But believe me, we're used to it—and it's a very valuable thing to hear," says Dr. Palmiter.

Even close relationships sometimes fail to get at the right issues. Victoria Maxwell, 44, an actress and blogger from Half Moon Bay, British Columbia, says she worked with a therapist for 2½-years as a teenager and liked her enormously. But she never made much progress, because the therapist didn't recognize Ms. Maxwell's underlying bipolar disorder. "I became a really insightful depressed person. But it wasn't helping my depression," she says.

Years later, after several hospitalizations, a nurse referred Ms. Maxwell to an older psychiatrist. She initially thought they'd be a bad fit—but found he was the only one who believed she could have both a profound spiritual experience and bipolar disorder. "I trusted him, so I was willing to try what he suggested, which included medication," she says. "I wouldn't be where I am today without his help and understanding."

Setting measurable goals is crucial for knowing whether a therapy is working. In Ms. Maxwell's case, her psychiatrist said, "I think you're capable of moving out of your parents' home, living with roommates and driving a car—and I was," she says.

Finding the best therapist can be confusing

Patricia Wen : Boston Globe : February 4, 2013

A Dedham mother remembers when her teenage daughter became overwhelmed with anxiety and was using illicit drugs. When her daughter’s doctor suggested she see “a therapist,” the mother began investigating, and soon found a dizzying array of options — psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and social workers, among others.

Some specialized in prescribing mood-altering medications, while others focused on psychotherapy that delves into the child’s past. Some focused on changing destructive behaviors, while others probed family and school stresses. Beyond that, there were also pastoral counselors, yoga therapists, and life coaches.

“I used to think all therapists were the same,” said the mother, who asked to remain anonymous to protect her child’s identity.

“See a therapist” has become standard advice to many going through periods of anguish. Whether they’re victims or bystanders coping with traumatic events such as school shootings and natural disasters, or individuals going through a divorce or losing a job, some 13 percent of Americans use mental health services each year. These clinicians are in short supply nationwide, though Greater Boston — and the Northeast in general — has more than in most parts of the country. Among the available providers comes a confusing blizzard of options — and terminology.

“Terms like therapist, counselor, or psychotherapist are not regulated,” said Elana Eisman, executive director of the Massachusetts Psychological Association, which represents some 1,700 psychologists in the state. “Anyone can use those terms.”

In Massachusetts, however, not just anyone can promote themselves as a psychiatrist, psychologist, mental health counselor, or marriage and family therapist — professions that are licensed and regulated by the state with established educational and training standards. And though most health insurers will cover treatment provided by most state-licensed mental health professionals, some are excluded, such as certain types of licensed social workers with less training and education.

Finding the best therapist is not an easy task. Many mental health advocates say that patients should look for only state-licensed practitioners. The oversight of the state board, they say, ensures the clinician meets eligibility standards, and exposes them to investigation and possible disciplinary action if they are targets of complaints.

Alternative mental health treatments generally fall outside licensing and insurance systems, for better or worse. John Kepner, executive director of the International Association of Yoga Therapists, describes his area as an “emerging field” that promotes physical and emotional well-being, and says many suffering from stress-related ailments have been aided by yoga therapists. He said his group is working on establishing professional standards.

Though state licensing may have its benefits, he said, he’s ambivalent about the spiritual principles of yoga getting entangled in the bureaucracy of government regulations.

“Yoga and licensing are uneasy bedfellows,” he said.

Another issue to consider is the privacy of confidential information shared during therapy sessions. While state-licensed mental health practitioners covered under insurance are required to comply with federal laws limiting the disclosure of private information to others, alternative practitioners may be excluded or fall in the “gray space” of these laws, said Mark Schreiber, a Boston attorney who specializes in, among other things, medical privacy laws.

Mental health advocates say people need to consider many questions when looking for a therapist — and whether it’s a psychologist with a doctoral degree or a mental health counselor with a master’s may not be the most pressing issue.

Given tight budgets for most people, Larry DeAngelo, a staffer for the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Massachusetts, advises that most people first see what their insurance will cover, what clinicians fall under the insurer’s plan, and if specific clinicians have room for new patients. Availability remains tight, he said, and the debate over what type of therapist someone wants to see can almost be a luxury.

“It’s like when people are desperately starving, and you ask — do you want a chocolate bar or ice cream?” DeAngelo said.

Though insurers have come under fire for low reimbursement rates for behavioral health clinicians — as compared with those providing medical services for physical problems — many insist they are committed to giving members broad coverage from a wide variety of professionals.

For instance, Michael Sherman, chief medical officer for Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, said his company, as a general rule, pays for treatment administered by state-licensed mental health clinicians with advanced degrees who can practice without supervision. By that standard, over the past decade, Harvard Pilgrim began reimbursing licensed independent social workers, mental health counselors, and marriage and family therapists.

According to many mental health specialists, anyone seeking therapy services should first see a primary care doctor (or a pediatrician in the case of a child) to rule out any physical ailment to explain the emotional distress. For instance, some hormonal or neurological problems can explain depression or mood issues. Once a physical problem is ruled out, then a doctor can often help advise the patient about what type of therapist is best suited for their specific issue — such as a psychiatrist who can prescribe medications if bipolar illness is a possibility, a social worker if school troubles loom large, or a marriage and family therapist if divorce is on the horizon.

Eisman, of the Massachusetts Psychological Association, said there is also the intangible of chemistry between a patient and clinician — no matter if they have a MD, PhD, or LICSW after their name. She said any good clinician has had his or her share of therapeutic relationships that just didn’t work, and often can facilitate a better referral if necessary.

“Therapy works best when you can talk honestly,” she said.

Patricia Wen : Boston Globe : February 4, 2013

A Dedham mother remembers when her teenage daughter became overwhelmed with anxiety and was using illicit drugs. When her daughter’s doctor suggested she see “a therapist,” the mother began investigating, and soon found a dizzying array of options — psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and social workers, among others.

Some specialized in prescribing mood-altering medications, while others focused on psychotherapy that delves into the child’s past. Some focused on changing destructive behaviors, while others probed family and school stresses. Beyond that, there were also pastoral counselors, yoga therapists, and life coaches.

“I used to think all therapists were the same,” said the mother, who asked to remain anonymous to protect her child’s identity.

“See a therapist” has become standard advice to many going through periods of anguish. Whether they’re victims or bystanders coping with traumatic events such as school shootings and natural disasters, or individuals going through a divorce or losing a job, some 13 percent of Americans use mental health services each year. These clinicians are in short supply nationwide, though Greater Boston — and the Northeast in general — has more than in most parts of the country. Among the available providers comes a confusing blizzard of options — and terminology.

“Terms like therapist, counselor, or psychotherapist are not regulated,” said Elana Eisman, executive director of the Massachusetts Psychological Association, which represents some 1,700 psychologists in the state. “Anyone can use those terms.”

In Massachusetts, however, not just anyone can promote themselves as a psychiatrist, psychologist, mental health counselor, or marriage and family therapist — professions that are licensed and regulated by the state with established educational and training standards. And though most health insurers will cover treatment provided by most state-licensed mental health professionals, some are excluded, such as certain types of licensed social workers with less training and education.

Finding the best therapist is not an easy task. Many mental health advocates say that patients should look for only state-licensed practitioners. The oversight of the state board, they say, ensures the clinician meets eligibility standards, and exposes them to investigation and possible disciplinary action if they are targets of complaints.

Alternative mental health treatments generally fall outside licensing and insurance systems, for better or worse. John Kepner, executive director of the International Association of Yoga Therapists, describes his area as an “emerging field” that promotes physical and emotional well-being, and says many suffering from stress-related ailments have been aided by yoga therapists. He said his group is working on establishing professional standards.

Though state licensing may have its benefits, he said, he’s ambivalent about the spiritual principles of yoga getting entangled in the bureaucracy of government regulations.

“Yoga and licensing are uneasy bedfellows,” he said.

Another issue to consider is the privacy of confidential information shared during therapy sessions. While state-licensed mental health practitioners covered under insurance are required to comply with federal laws limiting the disclosure of private information to others, alternative practitioners may be excluded or fall in the “gray space” of these laws, said Mark Schreiber, a Boston attorney who specializes in, among other things, medical privacy laws.

Mental health advocates say people need to consider many questions when looking for a therapist — and whether it’s a psychologist with a doctoral degree or a mental health counselor with a master’s may not be the most pressing issue.

Given tight budgets for most people, Larry DeAngelo, a staffer for the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Massachusetts, advises that most people first see what their insurance will cover, what clinicians fall under the insurer’s plan, and if specific clinicians have room for new patients. Availability remains tight, he said, and the debate over what type of therapist someone wants to see can almost be a luxury.

“It’s like when people are desperately starving, and you ask — do you want a chocolate bar or ice cream?” DeAngelo said.

Though insurers have come under fire for low reimbursement rates for behavioral health clinicians — as compared with those providing medical services for physical problems — many insist they are committed to giving members broad coverage from a wide variety of professionals.

For instance, Michael Sherman, chief medical officer for Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, said his company, as a general rule, pays for treatment administered by state-licensed mental health clinicians with advanced degrees who can practice without supervision. By that standard, over the past decade, Harvard Pilgrim began reimbursing licensed independent social workers, mental health counselors, and marriage and family therapists.

According to many mental health specialists, anyone seeking therapy services should first see a primary care doctor (or a pediatrician in the case of a child) to rule out any physical ailment to explain the emotional distress. For instance, some hormonal or neurological problems can explain depression or mood issues. Once a physical problem is ruled out, then a doctor can often help advise the patient about what type of therapist is best suited for their specific issue — such as a psychiatrist who can prescribe medications if bipolar illness is a possibility, a social worker if school troubles loom large, or a marriage and family therapist if divorce is on the horizon.

Eisman, of the Massachusetts Psychological Association, said there is also the intangible of chemistry between a patient and clinician — no matter if they have a MD, PhD, or LICSW after their name. She said any good clinician has had his or her share of therapeutic relationships that just didn’t work, and often can facilitate a better referral if necessary.

“Therapy works best when you can talk honestly,” she said.

Will You Be My Therapist? Expert Advice on Finding the Right One

Elizabeth Bernstein : WSJ : September 23, 2014

People write me from time to time to ask, "How do I find a good therapist?"

I went to Prudence Gourguechon, a Chicago psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and past-president of the American Psychoanalytic Association, to find out what people entering therapy should look for in a therapist, how to establish the relationship and what the best ways are to work together to maximize treatment.

To find a therapist to try out, Dr. Gourguechon recommends asking friends if they know of someone they can recommend. If a friend has his or her own therapist, ask the friend to ask the therapist for a referral. Refrain from seeing the same therapist that a close friend or family member sees.

If you can't find a word-of-mouth recommendation, she suggests using a website such as Psychology Today; professionals post information about themselves on its "Find a Therapist" feature. When you see a promising listing, check out the therapist's website. Does he or she write well and view things similarly to how you do?

At the first meeting, Dr. Gourguechon says, pay attention to the fit. Are you comfortable with the office environment and the person's style of relating? Do you get the sense the therapist has a good preliminary understanding of what you are going through? "You should feel that they are tuned in and on your wave length, and that you can expect the relationship and understanding to deepen," Dr. Gourguechon says.

Within the first few meetings, the therapist should take a thorough history, give you a diagnosis and articulate how he or she can help. "They need to come up with something of a formulation that says: 'This is what I think your problem is, this is how I think it developed and this is what I can offer you," Dr. Gourguechon says. There should be a treatment plan—specifying how often you will meet, for how long and what type of therapy you will have, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or psychoanalysis.

The therapist also should be able to acknowledge his or her limitations. For example, if you have a major mental illness and you go see someone who does cognitive behavioral therapy, he should explain that while this therapy is helpful with many issues, you may need more help.

Like good physicians, effective therapists are good listeners. "You want an open-minded person who doesn't put you in their box, but gets to know you in all your complexity," Dr. Gourguechon says. "You want to hear: 'Let's keep talking.' You want to hear uncertainty—'It could be this or it could be that.' You want to hear an exploratory, curious stance."

"It's like when you go to a financial planner," she adds. "You can tell if they are really thinking about your needs and who you are as a person, or if they are just trying to sell you a product with the littlest effort."

As a patient, it is your job to participate in the process, Dr. Gourguechon says: "You are not there to receive wisdom or a bolt from the sky. You want expertise. But in many ways you share in the expertise."

Dr. Gourguechon's tips for maximizing the therapeutic relationship:

Don't edit yourself in therapy. Let thoughts float to the surface. This will help your therapist understand what is really bothering you the most, on an unconscious level.

Find out what your therapist wants you to do, and try to do it. If you have difficulties with any of it, talk about them. Don't pretend you are going to try a suggestion if you aren't actually going to try it. Don't pretend something is working.

Ask questions. If you don't understand something your therapist says, ask him or her to clarify. If something isn't helping, or you don't feel better, ask why not. Your therapist should be able to give you an explanation.

Give your therapist feedback. He or she will make a lot of suggestions and interpretations. Some will be good and some won't, Dr. Gourguechon says. Share your reactions, both positive and negative.

"Some people think just coming to therapy is going to change things for them, but it doesn't work that way," Dr. Gourguechon says. "You have to venture out trying to change, and then come back with reports on what is working and what isn't working. It's an active process, where there are constant adjustments on both the patient's and the therapist's part."

And how can you tell if you've gone as far as you can with your therapist—that it's time to break up? If you feel that your therapy has stalled, the first thing to do is talk to your therapist about it, Dr. Gourguechon says. Ask why he or she thinks it isn't working and request an updated treatment plan. Your therapist should take you seriously and not become defensive. You might not like the answer ("Sometimes it takes a long time to change"), but you should get a clear one.

"If they say, 'Just keep coming and we will keep doing the same thing—and they have no rationale for why you will feel different in a year when you haven't yet—that's not too promising," Dr. Gourguechon says.

Of course, sometimes it can be part of therapy to get angry. You'll need to talk that through with your therapist and examine together whether you are recreating a pattern.

Another option, if you feel stalled, is to tell your therapist you want a second opinion and see what kind of response you get. "They should say, 'That's great, let's see what someone else thinks,' " Dr. Gourguechon says.

One big indication it may be time to leave: A relationship that feels empty, one-sided or like an ordinary friendship. "The therapeutic relationship should be a challenge. You should be learning new things about yourself," Dr. Gourguechon says. "Maybe not every day or every week, but pretty consistently. There should be progression."

Elizabeth Bernstein : WSJ : September 23, 2014

People write me from time to time to ask, "How do I find a good therapist?"

I went to Prudence Gourguechon, a Chicago psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and past-president of the American Psychoanalytic Association, to find out what people entering therapy should look for in a therapist, how to establish the relationship and what the best ways are to work together to maximize treatment.

To find a therapist to try out, Dr. Gourguechon recommends asking friends if they know of someone they can recommend. If a friend has his or her own therapist, ask the friend to ask the therapist for a referral. Refrain from seeing the same therapist that a close friend or family member sees.

If you can't find a word-of-mouth recommendation, she suggests using a website such as Psychology Today; professionals post information about themselves on its "Find a Therapist" feature. When you see a promising listing, check out the therapist's website. Does he or she write well and view things similarly to how you do?

At the first meeting, Dr. Gourguechon says, pay attention to the fit. Are you comfortable with the office environment and the person's style of relating? Do you get the sense the therapist has a good preliminary understanding of what you are going through? "You should feel that they are tuned in and on your wave length, and that you can expect the relationship and understanding to deepen," Dr. Gourguechon says.

Within the first few meetings, the therapist should take a thorough history, give you a diagnosis and articulate how he or she can help. "They need to come up with something of a formulation that says: 'This is what I think your problem is, this is how I think it developed and this is what I can offer you," Dr. Gourguechon says. There should be a treatment plan—specifying how often you will meet, for how long and what type of therapy you will have, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or psychoanalysis.

The therapist also should be able to acknowledge his or her limitations. For example, if you have a major mental illness and you go see someone who does cognitive behavioral therapy, he should explain that while this therapy is helpful with many issues, you may need more help.

Like good physicians, effective therapists are good listeners. "You want an open-minded person who doesn't put you in their box, but gets to know you in all your complexity," Dr. Gourguechon says. "You want to hear: 'Let's keep talking.' You want to hear uncertainty—'It could be this or it could be that.' You want to hear an exploratory, curious stance."

"It's like when you go to a financial planner," she adds. "You can tell if they are really thinking about your needs and who you are as a person, or if they are just trying to sell you a product with the littlest effort."

As a patient, it is your job to participate in the process, Dr. Gourguechon says: "You are not there to receive wisdom or a bolt from the sky. You want expertise. But in many ways you share in the expertise."

Dr. Gourguechon's tips for maximizing the therapeutic relationship:

Don't edit yourself in therapy. Let thoughts float to the surface. This will help your therapist understand what is really bothering you the most, on an unconscious level.

Find out what your therapist wants you to do, and try to do it. If you have difficulties with any of it, talk about them. Don't pretend you are going to try a suggestion if you aren't actually going to try it. Don't pretend something is working.

Ask questions. If you don't understand something your therapist says, ask him or her to clarify. If something isn't helping, or you don't feel better, ask why not. Your therapist should be able to give you an explanation.

Give your therapist feedback. He or she will make a lot of suggestions and interpretations. Some will be good and some won't, Dr. Gourguechon says. Share your reactions, both positive and negative.

"Some people think just coming to therapy is going to change things for them, but it doesn't work that way," Dr. Gourguechon says. "You have to venture out trying to change, and then come back with reports on what is working and what isn't working. It's an active process, where there are constant adjustments on both the patient's and the therapist's part."

And how can you tell if you've gone as far as you can with your therapist—that it's time to break up? If you feel that your therapy has stalled, the first thing to do is talk to your therapist about it, Dr. Gourguechon says. Ask why he or she thinks it isn't working and request an updated treatment plan. Your therapist should take you seriously and not become defensive. You might not like the answer ("Sometimes it takes a long time to change"), but you should get a clear one.

"If they say, 'Just keep coming and we will keep doing the same thing—and they have no rationale for why you will feel different in a year when you haven't yet—that's not too promising," Dr. Gourguechon says.

Of course, sometimes it can be part of therapy to get angry. You'll need to talk that through with your therapist and examine together whether you are recreating a pattern.

Another option, if you feel stalled, is to tell your therapist you want a second opinion and see what kind of response you get. "They should say, 'That's great, let's see what someone else thinks,' " Dr. Gourguechon says.

One big indication it may be time to leave: A relationship that feels empty, one-sided or like an ordinary friendship. "The therapeutic relationship should be a challenge. You should be learning new things about yourself," Dr. Gourguechon says. "Maybe not every day or every week, but pretty consistently. There should be progression."

How to Give Your Therapist Feedback

We often think of psychotherapists as “all-knowing,” which can make patients feel that complaining about the therapy or the therapist is not allowed.

By Juli Fraga and Hilary Jacobs Hendel : NY Times : Aug. 1, 2019

As with any relationship, patient and therapist unions aren’t immune to misunderstandings. When conflict appears, addressing it early on can help patients determine if the therapist and the therapy are right for them.

We often think of psychotherapists as “all-knowing,” which can make patients feel that complaining about the therapy or the therapist is not allowed.

But numerous studies have found that providing feedback pays off. According to psychology researchers, patient feedback can bolster the “therapeutic alliance.”

Similar to relationship chemistry, a sturdy alliance between patients and their therapists includes openness, trust, and collaboration, and according to the American Psychological Association, it’s essential to meeting treatment goals. Regardless of the type of therapy one receives, it’s this connection — the bedrock from which hope springs — that matters most of all.

In their 2015 book, “Premature Termination in Psychotherapy: Strategies for Engaging Clients and Improving Outcomes,” the psychologists Joshua K. Swift and Roger Greenberg point out that unrealistic expectations about treatment, compatibility issues with the therapist and fear of facing painful experiences can cause patients to stop therapy prematurely.

Indeed, studies suggest that 20 percent of patients getting mental health care will end therapy too soon — often without telling their therapists why.

For patients wondering how to give their therapists feedback, here are some suggestions.

Be Direct About Your ConcernsFrom talking too much or not enough to mislabeling feelings and offering unsolicited advice, therapists may unintentionally upset their patients in various ways. When this happens, broaching the topic by saying, “I’d like to discuss how I feel about coming to therapy,” or “Your recommendations aren’t helpful — here’s why,” are two ways to begin the conversation.

It’s often challenging for patients to be upfront about their therapy concerns when bringing up sensitive topics, research by the psychologists Matt Blanchard and Barry A. Farber suggests.

In one 2016 study, they found that 72.6 percent of psychotherapy patients had lied about their therapy experience. Common lies included pretending to agree with the therapist’s suggestions, pretending to find treatment helpful and masking their opinion of the therapist.

In therapy, these white lies can rupture treatment because it means the patient’s needs aren’t being met. This is why it’s crucial for patients to discuss any negative or unsettling feelings that ensue during therapy.

Perhaps the therapist came across as judgmental, started the session late or didn’t provide a structured treatment plan. Whatever the therapist’s mistake, patients can be direct by stating why they are upset.

When giving feedback, it’s common to pad critical comments with compliments. Organizational psychologists warn these positive statements, known as a “feedback sandwich,” can drown out negative messages.

The same pattern can play out in therapy. Before sharing their misgivings, patients may feel the need to say something positive, as a way to protect the therapist’s feelings. But while therapists are trained to look out for their client’s well-being, patients don’t need to do the same.

If a patient feels hurt by the therapist’s words, it’s O.K. to say, “I’m hurt by what you said, and I’d like to discuss it with you.” If the therapist is sharing too much personal information, patients can set a boundary by saying, “I prefer not to hear your personal stories because I’m here to work on myself.”

Analyze the Therapist’s ResponseThe therapist should be receptive to feedback. Positive and empathic responses may include apologizing for the misunderstanding, suggesting ways to improve therapy, as well as exploring what it’s like for the patient to speak up and commending their courage for doing so.

But not all therapists respond to feedback professionally. Some may label the patient’s behavior as “resistant,” or incorrectly link the patient’s complaints to unresolved psychological issues. In addition, therapists who become defensive, angry or judgmental when receiving patient feedback may do more harm than good. In these instances, patients may be better off finding a different therapist.

Collaborate Toward a SolutionOnce grievances are aired, the stage is set to work toward a possible solution, which may be informed by the type of treatment.

Therapists viewing the therapeutic relationship as a focal point of treatment, known as client-centered, psychodynamic or attachment-oriented therapy, see feedback as an opportunity to strengthen the patient-therapist alliance.

To do this, they acknowledge the patient’s disappointment, anger and frustration. Curious to learn how therapy went off course, these therapists also invite their patients to share more. Because a person’s emotional reaction may offer clues about the nature of their suffering, client-centered therapists might also probe whether the patient’s negative feelings have roots in childhood experiences or traumas. To ease future treatment anxiety, these therapists often say, “If I do or say anything that makes you uncomfortable, I want you to let me know.”

On the other hand, behavioral therapists may meet patient feedback by introducing mental health questionnaires, as a way to collect data about treatment progress. They may also ask their patients to complete behavioral exercises outside of therapy. Doing so allows the therapist to see if the patient’s symptoms are improving and to make adjustments, as needed.

While solutions vary, patients should feel that their needs have been met, and that continuing treatment is worthwhile.

Check InAfter establishing an open collaboration where feedback is welcome, checking in about the agreed-upon solution or the new treatment plan can help keep therapy on track. Saying, “I’d like to revisit my progress in a couple of weeks,” or “Can I let you know if I feel misunderstood in the future?” are useful questions and reminders.

Unlike fixing a broken bone, healing a patient’s emotional pain isn’t always straightforward, which means patients may feel ambivalent about treatment (even after giving feedback) or become anxious when sharing vulnerable details about childhood abuse, grief, severe depression or intimacy issues.

While numerous psychological interventions can teach patients how to alter their behaviors and face their fears, according to the researcher and psychologist Dr. Allan Schore, ultimately, it’s the emotional communication between patient and therapist that’s curative.

What feedback offers is an opportunity for realness and deeper intimacy with one’s therapist. When this happens, patients can feel seen and heard, which can be a turning point in treatment, as well as in life.

We often think of psychotherapists as “all-knowing,” which can make patients feel that complaining about the therapy or the therapist is not allowed.

By Juli Fraga and Hilary Jacobs Hendel : NY Times : Aug. 1, 2019

As with any relationship, patient and therapist unions aren’t immune to misunderstandings. When conflict appears, addressing it early on can help patients determine if the therapist and the therapy are right for them.

We often think of psychotherapists as “all-knowing,” which can make patients feel that complaining about the therapy or the therapist is not allowed.

But numerous studies have found that providing feedback pays off. According to psychology researchers, patient feedback can bolster the “therapeutic alliance.”

Similar to relationship chemistry, a sturdy alliance between patients and their therapists includes openness, trust, and collaboration, and according to the American Psychological Association, it’s essential to meeting treatment goals. Regardless of the type of therapy one receives, it’s this connection — the bedrock from which hope springs — that matters most of all.

In their 2015 book, “Premature Termination in Psychotherapy: Strategies for Engaging Clients and Improving Outcomes,” the psychologists Joshua K. Swift and Roger Greenberg point out that unrealistic expectations about treatment, compatibility issues with the therapist and fear of facing painful experiences can cause patients to stop therapy prematurely.

Indeed, studies suggest that 20 percent of patients getting mental health care will end therapy too soon — often without telling their therapists why.

For patients wondering how to give their therapists feedback, here are some suggestions.

Be Direct About Your ConcernsFrom talking too much or not enough to mislabeling feelings and offering unsolicited advice, therapists may unintentionally upset their patients in various ways. When this happens, broaching the topic by saying, “I’d like to discuss how I feel about coming to therapy,” or “Your recommendations aren’t helpful — here’s why,” are two ways to begin the conversation.

It’s often challenging for patients to be upfront about their therapy concerns when bringing up sensitive topics, research by the psychologists Matt Blanchard and Barry A. Farber suggests.

In one 2016 study, they found that 72.6 percent of psychotherapy patients had lied about their therapy experience. Common lies included pretending to agree with the therapist’s suggestions, pretending to find treatment helpful and masking their opinion of the therapist.

In therapy, these white lies can rupture treatment because it means the patient’s needs aren’t being met. This is why it’s crucial for patients to discuss any negative or unsettling feelings that ensue during therapy.

Perhaps the therapist came across as judgmental, started the session late or didn’t provide a structured treatment plan. Whatever the therapist’s mistake, patients can be direct by stating why they are upset.

When giving feedback, it’s common to pad critical comments with compliments. Organizational psychologists warn these positive statements, known as a “feedback sandwich,” can drown out negative messages.

The same pattern can play out in therapy. Before sharing their misgivings, patients may feel the need to say something positive, as a way to protect the therapist’s feelings. But while therapists are trained to look out for their client’s well-being, patients don’t need to do the same.

If a patient feels hurt by the therapist’s words, it’s O.K. to say, “I’m hurt by what you said, and I’d like to discuss it with you.” If the therapist is sharing too much personal information, patients can set a boundary by saying, “I prefer not to hear your personal stories because I’m here to work on myself.”

Analyze the Therapist’s ResponseThe therapist should be receptive to feedback. Positive and empathic responses may include apologizing for the misunderstanding, suggesting ways to improve therapy, as well as exploring what it’s like for the patient to speak up and commending their courage for doing so.

But not all therapists respond to feedback professionally. Some may label the patient’s behavior as “resistant,” or incorrectly link the patient’s complaints to unresolved psychological issues. In addition, therapists who become defensive, angry or judgmental when receiving patient feedback may do more harm than good. In these instances, patients may be better off finding a different therapist.

Collaborate Toward a SolutionOnce grievances are aired, the stage is set to work toward a possible solution, which may be informed by the type of treatment.

Therapists viewing the therapeutic relationship as a focal point of treatment, known as client-centered, psychodynamic or attachment-oriented therapy, see feedback as an opportunity to strengthen the patient-therapist alliance.

To do this, they acknowledge the patient’s disappointment, anger and frustration. Curious to learn how therapy went off course, these therapists also invite their patients to share more. Because a person’s emotional reaction may offer clues about the nature of their suffering, client-centered therapists might also probe whether the patient’s negative feelings have roots in childhood experiences or traumas. To ease future treatment anxiety, these therapists often say, “If I do or say anything that makes you uncomfortable, I want you to let me know.”

On the other hand, behavioral therapists may meet patient feedback by introducing mental health questionnaires, as a way to collect data about treatment progress. They may also ask their patients to complete behavioral exercises outside of therapy. Doing so allows the therapist to see if the patient’s symptoms are improving and to make adjustments, as needed.

While solutions vary, patients should feel that their needs have been met, and that continuing treatment is worthwhile.

Check InAfter establishing an open collaboration where feedback is welcome, checking in about the agreed-upon solution or the new treatment plan can help keep therapy on track. Saying, “I’d like to revisit my progress in a couple of weeks,” or “Can I let you know if I feel misunderstood in the future?” are useful questions and reminders.

Unlike fixing a broken bone, healing a patient’s emotional pain isn’t always straightforward, which means patients may feel ambivalent about treatment (even after giving feedback) or become anxious when sharing vulnerable details about childhood abuse, grief, severe depression or intimacy issues.

While numerous psychological interventions can teach patients how to alter their behaviors and face their fears, according to the researcher and psychologist Dr. Allan Schore, ultimately, it’s the emotional communication between patient and therapist that’s curative.

What feedback offers is an opportunity for realness and deeper intimacy with one’s therapist. When this happens, patients can feel seen and heard, which can be a turning point in treatment, as well as in life.

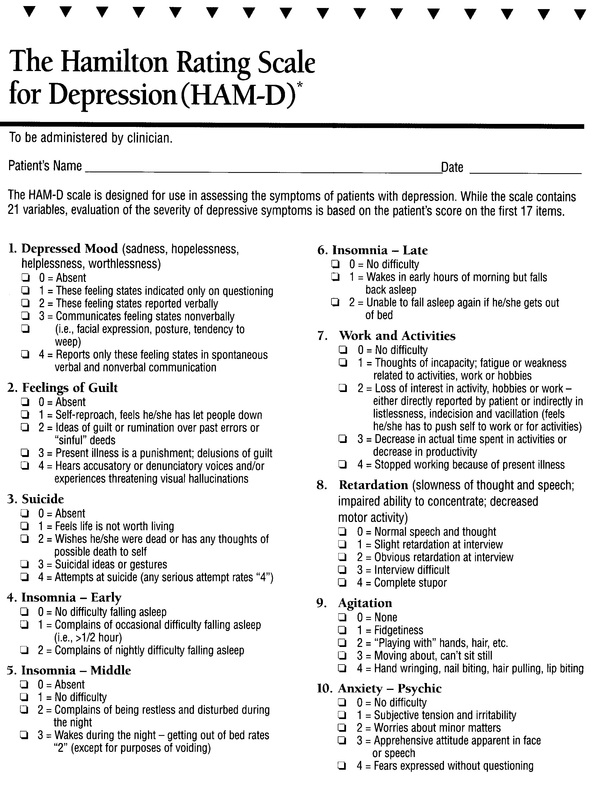

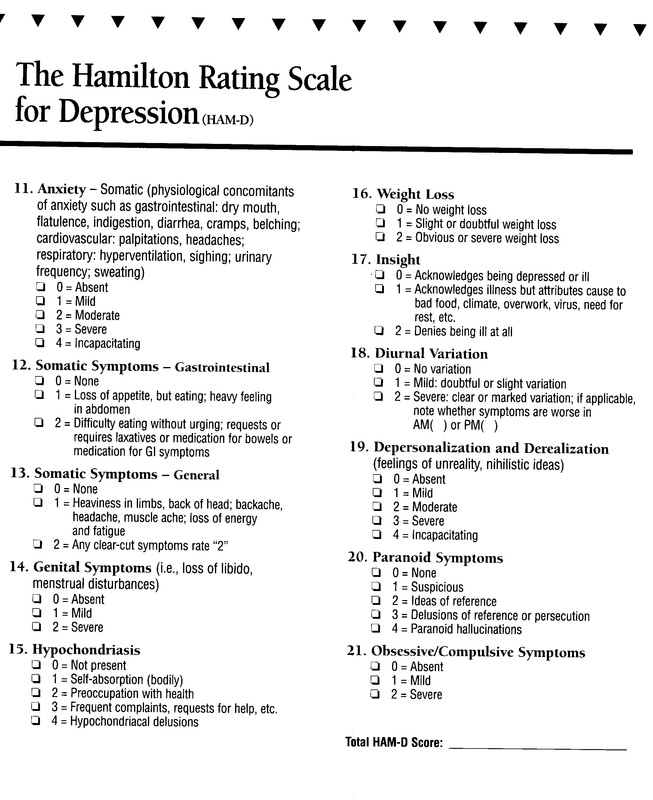

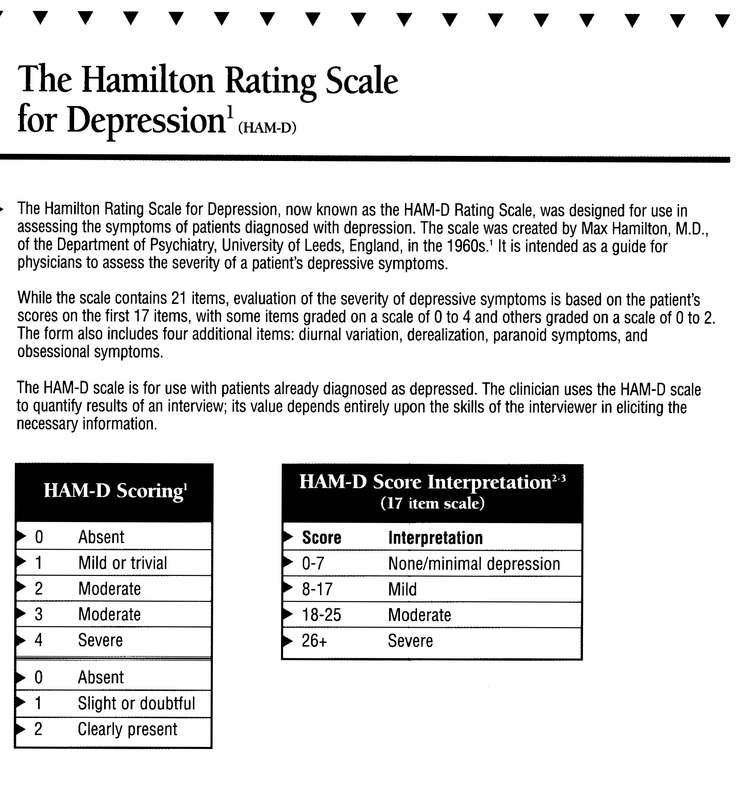

DEPRESSION SCREENING TEST

A Regular Checkup Is Good for the Mind as Well as the Body

By Ann Carrns : NY Times : November 13, 2012

Everyone is familiar with the concept of a periodic medical checkup — some sort of scheduled doctor’s visit to check your blood pressure, weight and other physical benchmarks.

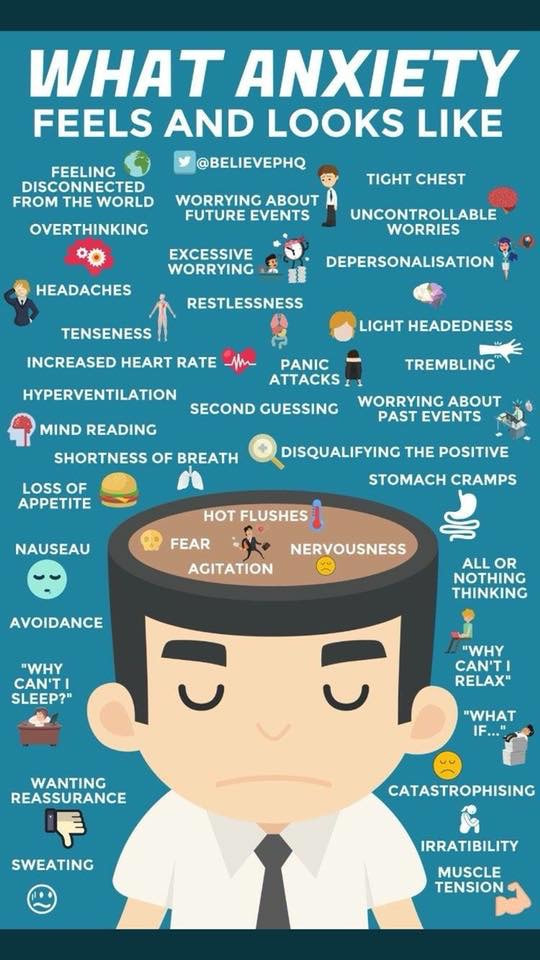

The notion of a regular mental health checkup is less established, perhaps because of the historical stigma about mental illness. But taking periodic stock of your emotional well-being can help identify warning signs of common ailments like depression or anxiety. Such illnesses are highly treatable, especially when they are identified in their early stages, before they get so severe that they precipitate some sort of personal — and perhaps financial — crisis.

“Absolutely, people should have a mental health checkup,” said Jeffrey Borenstein, editor in chief of Psychiatric News, published by the American Psychiatric Association. “It’s just as important as having a physical checkup.”

About a quarter of American adults suffer from some type of mental health problem each year, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and 6 percent suffer severe ailments, like schizophrenia or major depression. When left untreated, mental health illnesses are more likely to lead to hospitalization — something that could mean time lost from work.

Ideally, doctors should ask patients about their moods as part of a regular wellness visit, Dr. Borenstein said — there doesn’t necessarily need to be a special visit to gauge mental health. But if the doctor doesn’t bring it up, patients can educate themselves and start the conversation with their physicians.

Jeffrey Cain, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said family doctors were trained to spot symptoms of mental illness, like depression, and he encouraged patients to bring in questions or concerns for discussion. But people don’t necessarily go to their family doctor and say they are depressed, he said. Rather, they say they’re tired, or that they lack energy, that they’re having trouble concentrating or that their body aches — all of which can be symptoms of depression or anxiety.

There are some well-known screening tools that patients can use as a starting point to assess themselves, to help prompt a conversation with their doctor. Dr. Borenstein mentioned a common tool used by doctors to assess patients for depression: a “P.H.Q.,” for “patient health questionnaire” He cautioned that the idea here was not to self-diagnose using such forms — there are several versions, varying by number of questions — but rather to self-assess, and then discuss your concerns with a professional.

The P.H.Q.-9, which asks nine questions, was developed by researchers at Columbia University and Indiana University, with help from a grant from Pfizer Inc. The form is available on several Web sites, including (phqscreeners.com/pdfs/02_PHQ-9/English.pdf).

It asks about the patient’s outlook and health habits over the previous two weeks. The first question, for instance, asks patients whether they have had “little interest or pleasure” in doing things and asks them to check a box ranging from “not at all,” which scores a zero, to “nearly every day,” which scores a 3. A professional computes a total score, which gives more weight to frequent symptoms; the higher the score, the greater the likelihood of significant depression.

Another set of screening tools for depression and other mental health disorders were developed by Screening for Mental Health, a Boston-area nonprofit that creates assessment tools for use by health plans, colleges, the military and the general public. Founded by Douglas Jacobs, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, the organization grew out of the first National Depression Screening Day, which is held annually each October during Mental Illness Awareness Week.

Mental illnesses have specific signs and symptoms, much as a disease like diabetes does, Dr. Jacobs said, and those symptoms can be identified and treated. Take depression, again, as an example. It’s normal to be sad for a while after a personal loss or a traumatic event. But when the effects linger and begin to affect your self-esteem, or interfere with your ability to do your job or handle other responsibilities, he said, you may want to consider if you are suffering from a more serious depression that should be treated professionally — with behavioral therapy, medication or both.

At the site helpyourselfhelpothers.org, which is sponsored by Screening for Mental Health, you can find locations near you that offer mental health services. Or, you can use a free online screening tool that can help you gauge if you might be at risk for various illnesses including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.

You can choose a specific screening or answer questions to help narrow your choice. For instance, the tool asks you to complete the sentence “I have been...” with phrases like “feeling sad or empty,” or “drinking more than planned.”

The depression screening tool asks questions about how you have been feeling during the last two weeks, like whether you have been “blaming yourself for things” some of the time, all of the time, or most of the time.

The questionnaire concludes with a finding based on your answers. For instance, it might tell you that “Your screening results are consistent with symptoms of an eating disorder,” along with a recommendation to seek a professional evaluation. Gina N. Duncan, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Health Sciences University in Augusta, who has blogged about the notion of a personal mental health checkup, said sleep disruptions were often a sign of stress. If you’re sleeping much more or less than usual, or having difficulty falling asleep, that can be a warning signal..

Many large employers include mental health coverage as part of their health benefits packages, and recent federal rules on benefits “parity” mean such benefits at large plans should not have higher have co-payments and deductibles or stricter limits on treatment than benefits for other medical or surgical needs. Also, most large companies currently offer employee assistance plans, which provide counseling and referrals — both over the phone and in person — to workers and members of their families who are suffering from personal crises.

Helen B. Darling, president of the National Business Group on Health, a consortium of large employers, said employee assistance plans were an important way to screen for mental health problems. Help through them is generally provided free of charge outside of the main health insurance plan, so using the service does not generate an insurance claim.

Over all, however, 15 percent of employers in the United States do not offer mental health coverage to employees, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. Such benefits may become more widely available in 2014, when many provisions of the Affordable Care Act take effect. Mental health benefits will be part of the “essential package” that must be offered by many insurance plans, including the new state-sponsored insurance exchanges.

By Ann Carrns : NY Times : November 13, 2012

Everyone is familiar with the concept of a periodic medical checkup — some sort of scheduled doctor’s visit to check your blood pressure, weight and other physical benchmarks.

The notion of a regular mental health checkup is less established, perhaps because of the historical stigma about mental illness. But taking periodic stock of your emotional well-being can help identify warning signs of common ailments like depression or anxiety. Such illnesses are highly treatable, especially when they are identified in their early stages, before they get so severe that they precipitate some sort of personal — and perhaps financial — crisis.

“Absolutely, people should have a mental health checkup,” said Jeffrey Borenstein, editor in chief of Psychiatric News, published by the American Psychiatric Association. “It’s just as important as having a physical checkup.”

About a quarter of American adults suffer from some type of mental health problem each year, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and 6 percent suffer severe ailments, like schizophrenia or major depression. When left untreated, mental health illnesses are more likely to lead to hospitalization — something that could mean time lost from work.

Ideally, doctors should ask patients about their moods as part of a regular wellness visit, Dr. Borenstein said — there doesn’t necessarily need to be a special visit to gauge mental health. But if the doctor doesn’t bring it up, patients can educate themselves and start the conversation with their physicians.

Jeffrey Cain, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said family doctors were trained to spot symptoms of mental illness, like depression, and he encouraged patients to bring in questions or concerns for discussion. But people don’t necessarily go to their family doctor and say they are depressed, he said. Rather, they say they’re tired, or that they lack energy, that they’re having trouble concentrating or that their body aches — all of which can be symptoms of depression or anxiety.

There are some well-known screening tools that patients can use as a starting point to assess themselves, to help prompt a conversation with their doctor. Dr. Borenstein mentioned a common tool used by doctors to assess patients for depression: a “P.H.Q.,” for “patient health questionnaire” He cautioned that the idea here was not to self-diagnose using such forms — there are several versions, varying by number of questions — but rather to self-assess, and then discuss your concerns with a professional.

The P.H.Q.-9, which asks nine questions, was developed by researchers at Columbia University and Indiana University, with help from a grant from Pfizer Inc. The form is available on several Web sites, including (phqscreeners.com/pdfs/02_PHQ-9/English.pdf).

It asks about the patient’s outlook and health habits over the previous two weeks. The first question, for instance, asks patients whether they have had “little interest or pleasure” in doing things and asks them to check a box ranging from “not at all,” which scores a zero, to “nearly every day,” which scores a 3. A professional computes a total score, which gives more weight to frequent symptoms; the higher the score, the greater the likelihood of significant depression.

Another set of screening tools for depression and other mental health disorders were developed by Screening for Mental Health, a Boston-area nonprofit that creates assessment tools for use by health plans, colleges, the military and the general public. Founded by Douglas Jacobs, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, the organization grew out of the first National Depression Screening Day, which is held annually each October during Mental Illness Awareness Week.

Mental illnesses have specific signs and symptoms, much as a disease like diabetes does, Dr. Jacobs said, and those symptoms can be identified and treated. Take depression, again, as an example. It’s normal to be sad for a while after a personal loss or a traumatic event. But when the effects linger and begin to affect your self-esteem, or interfere with your ability to do your job or handle other responsibilities, he said, you may want to consider if you are suffering from a more serious depression that should be treated professionally — with behavioral therapy, medication or both.

At the site helpyourselfhelpothers.org, which is sponsored by Screening for Mental Health, you can find locations near you that offer mental health services. Or, you can use a free online screening tool that can help you gauge if you might be at risk for various illnesses including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.

You can choose a specific screening or answer questions to help narrow your choice. For instance, the tool asks you to complete the sentence “I have been...” with phrases like “feeling sad or empty,” or “drinking more than planned.”

The depression screening tool asks questions about how you have been feeling during the last two weeks, like whether you have been “blaming yourself for things” some of the time, all of the time, or most of the time.

The questionnaire concludes with a finding based on your answers. For instance, it might tell you that “Your screening results are consistent with symptoms of an eating disorder,” along with a recommendation to seek a professional evaluation. Gina N. Duncan, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Health Sciences University in Augusta, who has blogged about the notion of a personal mental health checkup, said sleep disruptions were often a sign of stress. If you’re sleeping much more or less than usual, or having difficulty falling asleep, that can be a warning signal..

Many large employers include mental health coverage as part of their health benefits packages, and recent federal rules on benefits “parity” mean such benefits at large plans should not have higher have co-payments and deductibles or stricter limits on treatment than benefits for other medical or surgical needs. Also, most large companies currently offer employee assistance plans, which provide counseling and referrals — both over the phone and in person — to workers and members of their families who are suffering from personal crises.

Helen B. Darling, president of the National Business Group on Health, a consortium of large employers, said employee assistance plans were an important way to screen for mental health problems. Help through them is generally provided free of charge outside of the main health insurance plan, so using the service does not generate an insurance claim.

Over all, however, 15 percent of employers in the United States do not offer mental health coverage to employees, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. Such benefits may become more widely available in 2014, when many provisions of the Affordable Care Act take effect. Mental health benefits will be part of the “essential package” that must be offered by many insurance plans, including the new state-sponsored insurance exchanges.