- HOME PAGE

- WELCOME TO BMA

- HIPAA AND PRIVACY PRACTICES

- "MYCHART" health portal

- MOUNT AUBURN HOSPITAL

- After Hours Emergency Calls

- PCP, NP and PA Profiles

- Our Specialists and Specialty Services

- MT AUBURN DIABETES CENTER

- ABOUT OUR OFFICE

- Being Our Patient

- REFERRALS : online request form

- Patient LIBRARY

- Turning 65? MEDICARE explained

- Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

- FIVE WISHES AND HEALTHCARE PROXY

- Social Work Care Coordination

- Quality Care Measures

- MACIPA

- BULLETIN BOARD

- In Memoriam

- Job opportunities

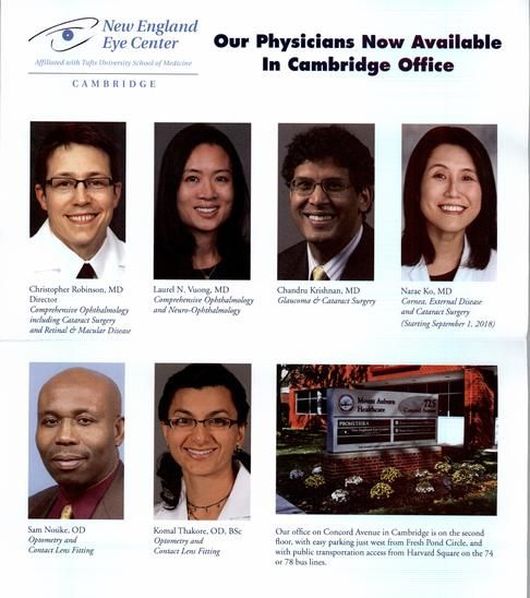

OPHTHALMOLOGY

While not part of Beth Israel Lahey Health Primary Care :

Belmont Medical Associates

we refer our patients to

New England Eye Center at Mount Auburn Hospital

is located on the second floor

Suite 2200, 725 Concord Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138

appointments can be made by calling

617-876-3660

www.neec.com

Christopher C. Robinson, MD

Chandru Krishnan, MD

Narae Ko, MD

Laurel N. Vuong, MD

Dr. Sam Nosike, OD

Dr. Komal Thakore, OD

Belmont Medical Associates

we refer our patients to

New England Eye Center at Mount Auburn Hospital

is located on the second floor

Suite 2200, 725 Concord Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138

appointments can be made by calling

617-876-3660

www.neec.com

Christopher C. Robinson, MD

Chandru Krishnan, MD

Narae Ko, MD

Laurel N. Vuong, MD

Dr. Sam Nosike, OD

Dr. Komal Thakore, OD

A look at what to do at what age for your eyes.

INFANTS: Eye exam at birth and again between 6 and 12 months.

PRESCHOOL: Get a visual acuity test between ages 3 and 3½. If the test shows misaligned eyes, lazy eye or refractive errors, such as nearsightedness, farsightedness or astigmatism, the child should see an eye doctor. It's important to treat these problems before age 7, when convergence, the ability of both eyes to focus on an object simultaneously, becomes more fully developed.

SCHOOL AGE: Eye screening should be done upon entering school and whenever a problem is suspected. Nearsightedness is the most common refractive error in this age group and can be corrected with eyeglasses.

TEENAGERS/20s: Vision development is complete by the time people reach their early 20s. It remains steady for several decades, and prescription lenses change only slightly or not at all. If you wear contact lenses, see your eye specialist yearly to check the prescription. Protect eyes while playing sports.

ADULTS UNDER 40: Since vision changes little, this is a good time for refractive or LASIK surgery. Get a complete eye exam once in the 20s and twice in 30s, but more often if you have family history of eye disease or wear contact lenses. Women may have vision fluctuations during pregnancy.

ADULTS 40 to 60: This is a time when symptoms of many eye diseases may begin to emerge. A comprehensive eye exam is recommended at age 40 to check for early signs of age-related macular degeneration and other problems. Most people will get presbyopia, an inability to focus on close-up objects, starting in their 40s, when the eye's lens gets less flexible.

65 AND UP: By age 65, 1 in 3 Americans will have a vision-impairing eye disease such as glaucoma and cataracts.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology

Tips for All Ages

INFANTS: Eye exam at birth and again between 6 and 12 months.

PRESCHOOL: Get a visual acuity test between ages 3 and 3½. If the test shows misaligned eyes, lazy eye or refractive errors, such as nearsightedness, farsightedness or astigmatism, the child should see an eye doctor. It's important to treat these problems before age 7, when convergence, the ability of both eyes to focus on an object simultaneously, becomes more fully developed.

SCHOOL AGE: Eye screening should be done upon entering school and whenever a problem is suspected. Nearsightedness is the most common refractive error in this age group and can be corrected with eyeglasses.

TEENAGERS/20s: Vision development is complete by the time people reach their early 20s. It remains steady for several decades, and prescription lenses change only slightly or not at all. If you wear contact lenses, see your eye specialist yearly to check the prescription. Protect eyes while playing sports.

ADULTS UNDER 40: Since vision changes little, this is a good time for refractive or LASIK surgery. Get a complete eye exam once in the 20s and twice in 30s, but more often if you have family history of eye disease or wear contact lenses. Women may have vision fluctuations during pregnancy.

ADULTS 40 to 60: This is a time when symptoms of many eye diseases may begin to emerge. A comprehensive eye exam is recommended at age 40 to check for early signs of age-related macular degeneration and other problems. Most people will get presbyopia, an inability to focus on close-up objects, starting in their 40s, when the eye's lens gets less flexible.

65 AND UP: By age 65, 1 in 3 Americans will have a vision-impairing eye disease such as glaucoma and cataracts.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology

Tips for All Ages

- People who wear contacts should see an eye specialist yearly.

- Get more frequent eye exams if you are diabetic or prediabetic.

- Regular exercise promotes blood circulation and oxygen intake important for eye health.

- Wear sunglasses—look for eyesun protection factor between 25 and 50—when outside in the sun.

- Rest up: During sleep, eyes are continuously lubricated and clear out irritants such as dust, allergens and smoke that accumulate during the day

Articles of interest:

The Best and Worst Habits for Eyesight

Are carrots good? Is blue light bad? Experts weigh in on nine common beliefs.

By Hannah Seo : May 15, 2023

If you were ever scolded as a child for reading in the dark, or if you have used blue-light-blocking glasses when working on a computer, you might have incorrect ideas about eye health.

About four in 10 adults in the United States are at high risk for vision loss, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But many eye conditions are treatable or preventable, said Dr. Joshua Ehrlich, an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Michigan.

Here are nine common beliefs people have about eye health, and what experts have to say about them.

1: Reading a book or looking at an electronic device up close is bad for your eyes.

True. Our eyes are not meant to focus on objects close to our face for long periods of time, said Dr. Xiaoying Zhu, an associate clinical professor of optometry and the lead myopia researcher at SUNY College of Optometry in New York City. When we do, especially as children, it encourages the eyeball to lengthen, which over time can cause nearsightedness, or myopia.

To help reduce the strain on your eyes, Dr. Zhu recommends following the 20-20-20 rule: After every 20 minutes of close reading, look at something at least 20 feet away for at least 20 seconds.

2: Reading in the dark can worsen your eyesight.

False. However, if the lighting is so dim that you need to hold your book or tablet close to your face, that can increase the risks mentioned above and create eyestrain, which can cause soreness around the eyes and temples, headache and difficulty concentrating. But these are usually temporary symptoms, Dr. Zhu said.

3: Spending more time outside helps eyesight.

True. Some research (mostly focused on children) suggests that outdoor time can reduce the risk of developing myopia, said Maria Liu, an associate professor of clinical optometry at the University of California, Berkeley. Experts don’t fully understand why this is, but some research suggests that bright sunlight may encourage the retina to produce dopamine, which discourages eye lengthening (though these experiments have mostly been conducted with animals, Dr. Zhu said).

4: Too much ultraviolet light can harm eyesight.

True. There is a reason experts say not to stare at the sun. Too much exposure to ultraviolet A and B rays in sunlight can “cause irreversible damage” to the retina, Dr. Ehrlich said. This can also increase your risk of developing cataracts, he said.

Too much UV light exposure can also increase the risk for developing cancers in the eye, Dr. Ehrlich said — though this risk is low. Wearing sunglasses, glasses or contacts that block UV rays can offer protection.

5: Taking a break from wearing glasses can prevent your eyesight from getting worse.

False. Some patients who need glasses tell Safal Khanal, an assistant professor in optometry and vision science at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, that they don’t wear their glasses all the time because they think it will make their condition worse. “That’s not true,” he said. If you need glasses, you should wear them.

6: Even a little blue light from screens is damaging to your eyes.

False. While some research has found that exposure to blue light can damage the retina and potentially cause vision problems over time, no solid evidence has confirmed that this happens with typical exposures in humans, Dr. Ehrlich said. There’s also no evidence that wearing blue-light-blocking glasses will improve eye health, he added.

But screens can be bad for eyesight in the other ways described above, including by causing dry eyes, Dr. Zhu said. “When we stare at a screen, we just don’t blink as often as we should,” she said, and that can cause eyestrain and temporary blurred vision.

7: Smoking is bad for eye health.

True. A 2011 C.D.C. study linked smoking with self-reported age-related eye diseases in older adults, including cataracts and age-related macular degeneration, a disease where part of the retina breaks down and blurs your vision. Toxic chemicals in cigarettes enter your bloodstream and damage sensitive tissues in the eyes including the retina, lens and macula, Dr. Khanal said.

8: Carrots are good for your eyes.

True. While a diet full of carrots won’t give you perfect vision, some evidence suggests that the nutrients in them are good for eye health. One large clinical trial, for instance, found that supplements containing nutrients found in carrots, including antioxidants like beta-carotene and vitamins C and E, could slow the progression of age-related macular degeneration.

Following an antioxidant-rich diet won’t necessarily prevent an eye disease from occurring, but it can be helpful “particularly for people with early macular degeneration,” Dr. Ehrlich said.

9: Worsening eyesight is an inevitable part of aging.

False. Most causes of declining eyesight in adulthood — including age-related macular degeneration, cataracts and glaucoma — are preventable or treatable if you catch them early, Dr. Ehrlich said. If your vision is starting to wane, don’t dismiss it as “just aging,” he added. Seeing an optometrist or ophthalmologist right away (or regularly, every year) will give you the best chance of staving off these conditions, he said.

Are carrots good? Is blue light bad? Experts weigh in on nine common beliefs.

By Hannah Seo : May 15, 2023

If you were ever scolded as a child for reading in the dark, or if you have used blue-light-blocking glasses when working on a computer, you might have incorrect ideas about eye health.

About four in 10 adults in the United States are at high risk for vision loss, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But many eye conditions are treatable or preventable, said Dr. Joshua Ehrlich, an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Michigan.

Here are nine common beliefs people have about eye health, and what experts have to say about them.

1: Reading a book or looking at an electronic device up close is bad for your eyes.

True. Our eyes are not meant to focus on objects close to our face for long periods of time, said Dr. Xiaoying Zhu, an associate clinical professor of optometry and the lead myopia researcher at SUNY College of Optometry in New York City. When we do, especially as children, it encourages the eyeball to lengthen, which over time can cause nearsightedness, or myopia.

To help reduce the strain on your eyes, Dr. Zhu recommends following the 20-20-20 rule: After every 20 minutes of close reading, look at something at least 20 feet away for at least 20 seconds.

2: Reading in the dark can worsen your eyesight.

False. However, if the lighting is so dim that you need to hold your book or tablet close to your face, that can increase the risks mentioned above and create eyestrain, which can cause soreness around the eyes and temples, headache and difficulty concentrating. But these are usually temporary symptoms, Dr. Zhu said.

3: Spending more time outside helps eyesight.

True. Some research (mostly focused on children) suggests that outdoor time can reduce the risk of developing myopia, said Maria Liu, an associate professor of clinical optometry at the University of California, Berkeley. Experts don’t fully understand why this is, but some research suggests that bright sunlight may encourage the retina to produce dopamine, which discourages eye lengthening (though these experiments have mostly been conducted with animals, Dr. Zhu said).

4: Too much ultraviolet light can harm eyesight.

True. There is a reason experts say not to stare at the sun. Too much exposure to ultraviolet A and B rays in sunlight can “cause irreversible damage” to the retina, Dr. Ehrlich said. This can also increase your risk of developing cataracts, he said.

Too much UV light exposure can also increase the risk for developing cancers in the eye, Dr. Ehrlich said — though this risk is low. Wearing sunglasses, glasses or contacts that block UV rays can offer protection.

5: Taking a break from wearing glasses can prevent your eyesight from getting worse.

False. Some patients who need glasses tell Safal Khanal, an assistant professor in optometry and vision science at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, that they don’t wear their glasses all the time because they think it will make their condition worse. “That’s not true,” he said. If you need glasses, you should wear them.

6: Even a little blue light from screens is damaging to your eyes.

False. While some research has found that exposure to blue light can damage the retina and potentially cause vision problems over time, no solid evidence has confirmed that this happens with typical exposures in humans, Dr. Ehrlich said. There’s also no evidence that wearing blue-light-blocking glasses will improve eye health, he added.

But screens can be bad for eyesight in the other ways described above, including by causing dry eyes, Dr. Zhu said. “When we stare at a screen, we just don’t blink as often as we should,” she said, and that can cause eyestrain and temporary blurred vision.

7: Smoking is bad for eye health.

True. A 2011 C.D.C. study linked smoking with self-reported age-related eye diseases in older adults, including cataracts and age-related macular degeneration, a disease where part of the retina breaks down and blurs your vision. Toxic chemicals in cigarettes enter your bloodstream and damage sensitive tissues in the eyes including the retina, lens and macula, Dr. Khanal said.

8: Carrots are good for your eyes.

True. While a diet full of carrots won’t give you perfect vision, some evidence suggests that the nutrients in them are good for eye health. One large clinical trial, for instance, found that supplements containing nutrients found in carrots, including antioxidants like beta-carotene and vitamins C and E, could slow the progression of age-related macular degeneration.

Following an antioxidant-rich diet won’t necessarily prevent an eye disease from occurring, but it can be helpful “particularly for people with early macular degeneration,” Dr. Ehrlich said.

9: Worsening eyesight is an inevitable part of aging.

False. Most causes of declining eyesight in adulthood — including age-related macular degeneration, cataracts and glaucoma — are preventable or treatable if you catch them early, Dr. Ehrlich said. If your vision is starting to wane, don’t dismiss it as “just aging,” he added. Seeing an optometrist or ophthalmologist right away (or regularly, every year) will give you the best chance of staving off these conditions, he said.

In Your Eyes: What They Reveal About Your Health

Shirley S. Wang : WSJ : August 13, 2012

As an ophthalmologist, David Ingvoldstad sees much more about his patients' health than just their eyes. Thanks to the clues the eyes provide, he regularly alerts patients to possible autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, monitors progression of their diabetes and once even suspected—correctly, as it turned out—that a patient had a brain tumor on the basis of the pattern of her vision changes.

Because the body's systems are interconnected, changes in the eye can reflect those in the vascular, nervous and immune system, among others. And because the eyes are see-through in a way other organs aren't, they offer a unique glimpse into the body. Blood vessels, nerves and tissue can all be viewed directly through the eye with specialized equipment.

The eyes are the window not only to the soul, but also to the health of the body. Shirley Wang on Lunch Break focuses on some of new research going on about the eye and what it means for seemingly unrelated disease.

With regular monitoring, eye doctors can be the first to spot certain medical conditions and can usher patients for further evaluation, potentially leading to earlier diagnosis and treatment. Clots in the tiny blood vessels of the retina can signal a risk for stroke, for example, and thickened blood-vessel walls along with narrowing of the vessels can signal high blood pressure. In some cases, examining the eye can help confirm some of the diagnoses or help differentiate disorders from each other.

"There's no question the eye has always been the window to the body," says Emily Chew, deputy director of the epidemiology division at the National Eye Institute. She adds, "Anybody with any visual changes…should be seeing someone right away."

Scientists are working to advance their knowledge of what the eye can reveal about diseases. For instance, researchers are studying how dark spots on the back of the eye known as CHRPE, or congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, are associated with certain forms of colon cancer, and how dementia-related changes are signaled in the eye, such as how the eye reacts to light. Other scientists, like Dr. Chew, are studying how to keep the eye healthier for longer, which could be good for the health of the eye as well as the rest of the body.

Companies are building enhanced technology that allow for better viewing of the eye. Scotland-based Optos, for example, created a machine that allows for better screening of the periphery of the retina. The machines can now be found in doctors' offices and research clinics. Instead of the typical 30-degree view of the eye, it offers a 200-degree view. Being able to see more of the periphery could mean earlier or more accurate diagnosis of various diseases and may also be coupled with intervention tools to improve treatment. Optos is currently funding a study of the use of retinal imaging to diagnose heart disease, according to Anne Marie Cairns, head of its clinical development.

The eye's job is to deliver vision by converting incoming light information into messages that the brain can understand. But problems in vision can indicate a problem outside of the eye itself.

One critical structure in the eye is the retina, which allows us to experience vision. It is made of brain tissue and contains many blood vessels. Changes in vessels in other parts of the body are reflected in the retina as well, sometimes more noticeably or sooner than elsewhere in the body.

The eyes can help predict stroke risk, particularly important to people with heart disease and other stroke risk factors. That is because blood clots in the arteries of the neck and head that might lead to stroke are often visible as retinal emboli, or clots, in the tiny blood vessels of the eye, according to the National Eye Institute.

The immune system's interaction with the eyes can be telling, too, yielding information about autoimmune diseases or infections in the rest of the body. Sometimes eye symptoms may appear before others, like joint pain, in patients.

For instance, inflammation in the optic nerve can signal problems in an otherwise healthy, young person. Along with decreased vision and sometimes pain, it can suggest multiple sclerosis. If the optic disc, a portion of the optic nerve, is swollen, and the patient has symmetrical decreased field of vision, such as a decreased right visual field in both eyes, they may need an evaluation for a brain tumor—a rare circumstance.

If immune cells like white blood cells are seen floating in the vitreous of the eye, it could signal a local eye infection or one that is spread throughout the body.

Diabetes is one disease that can cause major changes in the eye. In diabetic retinopathy, a common cause of blindness, blood vessels hemorrhage and leak blood and fluid. When blood vessels don't function properly, they can potentially cause eye tissue to be deprived of oxygen and to die, leaving permanent vision damage.

Also, in diabetic patients additional blood vessels may grow in the eye, anchoring themselves into the sticky gel known as the vitreous, which fills a cavity near the retina. This condition can cause further problems if the retina tears when it tries to separate from the vitreous—a common occurrence as people age—but is tangled by growth of new blood vessels.

Usually diabetic patients who come in for eye exams already know they have the disease, and the primary purpose of an eye exam is to make sure they don't have diabetic retinopathy or, if they did have it, that the condition hasn't progressed, say eye doctors like Dr. Ingvoldstad, a private practitioner at Midwest Eye Care in Omaha, Neb. But once in a while there is a patient who has noticed vision changes but didn't realize he or she had diabetes until alerted during an eye exam that there were signs of the eye disease that is consistent with the condition, he says.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends eye examinations whenever individuals notice any vision changes or injury. Adults with no symptoms or known risk factors for eye disease should get a base line exam by age 40 and return every two to four years for evaluations until their mid-50s. From 55 to 64, the AAO recommends exams every one to three years, and every one to two years for those 65 and older.

Shirley S. Wang : WSJ : August 13, 2012

As an ophthalmologist, David Ingvoldstad sees much more about his patients' health than just their eyes. Thanks to the clues the eyes provide, he regularly alerts patients to possible autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, monitors progression of their diabetes and once even suspected—correctly, as it turned out—that a patient had a brain tumor on the basis of the pattern of her vision changes.

Because the body's systems are interconnected, changes in the eye can reflect those in the vascular, nervous and immune system, among others. And because the eyes are see-through in a way other organs aren't, they offer a unique glimpse into the body. Blood vessels, nerves and tissue can all be viewed directly through the eye with specialized equipment.

The eyes are the window not only to the soul, but also to the health of the body. Shirley Wang on Lunch Break focuses on some of new research going on about the eye and what it means for seemingly unrelated disease.

With regular monitoring, eye doctors can be the first to spot certain medical conditions and can usher patients for further evaluation, potentially leading to earlier diagnosis and treatment. Clots in the tiny blood vessels of the retina can signal a risk for stroke, for example, and thickened blood-vessel walls along with narrowing of the vessels can signal high blood pressure. In some cases, examining the eye can help confirm some of the diagnoses or help differentiate disorders from each other.

"There's no question the eye has always been the window to the body," says Emily Chew, deputy director of the epidemiology division at the National Eye Institute. She adds, "Anybody with any visual changes…should be seeing someone right away."

Scientists are working to advance their knowledge of what the eye can reveal about diseases. For instance, researchers are studying how dark spots on the back of the eye known as CHRPE, or congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, are associated with certain forms of colon cancer, and how dementia-related changes are signaled in the eye, such as how the eye reacts to light. Other scientists, like Dr. Chew, are studying how to keep the eye healthier for longer, which could be good for the health of the eye as well as the rest of the body.

Companies are building enhanced technology that allow for better viewing of the eye. Scotland-based Optos, for example, created a machine that allows for better screening of the periphery of the retina. The machines can now be found in doctors' offices and research clinics. Instead of the typical 30-degree view of the eye, it offers a 200-degree view. Being able to see more of the periphery could mean earlier or more accurate diagnosis of various diseases and may also be coupled with intervention tools to improve treatment. Optos is currently funding a study of the use of retinal imaging to diagnose heart disease, according to Anne Marie Cairns, head of its clinical development.

The eye's job is to deliver vision by converting incoming light information into messages that the brain can understand. But problems in vision can indicate a problem outside of the eye itself.

One critical structure in the eye is the retina, which allows us to experience vision. It is made of brain tissue and contains many blood vessels. Changes in vessels in other parts of the body are reflected in the retina as well, sometimes more noticeably or sooner than elsewhere in the body.

The eyes can help predict stroke risk, particularly important to people with heart disease and other stroke risk factors. That is because blood clots in the arteries of the neck and head that might lead to stroke are often visible as retinal emboli, or clots, in the tiny blood vessels of the eye, according to the National Eye Institute.

The immune system's interaction with the eyes can be telling, too, yielding information about autoimmune diseases or infections in the rest of the body. Sometimes eye symptoms may appear before others, like joint pain, in patients.

For instance, inflammation in the optic nerve can signal problems in an otherwise healthy, young person. Along with decreased vision and sometimes pain, it can suggest multiple sclerosis. If the optic disc, a portion of the optic nerve, is swollen, and the patient has symmetrical decreased field of vision, such as a decreased right visual field in both eyes, they may need an evaluation for a brain tumor—a rare circumstance.

If immune cells like white blood cells are seen floating in the vitreous of the eye, it could signal a local eye infection or one that is spread throughout the body.

Diabetes is one disease that can cause major changes in the eye. In diabetic retinopathy, a common cause of blindness, blood vessels hemorrhage and leak blood and fluid. When blood vessels don't function properly, they can potentially cause eye tissue to be deprived of oxygen and to die, leaving permanent vision damage.

Also, in diabetic patients additional blood vessels may grow in the eye, anchoring themselves into the sticky gel known as the vitreous, which fills a cavity near the retina. This condition can cause further problems if the retina tears when it tries to separate from the vitreous—a common occurrence as people age—but is tangled by growth of new blood vessels.

Usually diabetic patients who come in for eye exams already know they have the disease, and the primary purpose of an eye exam is to make sure they don't have diabetic retinopathy or, if they did have it, that the condition hasn't progressed, say eye doctors like Dr. Ingvoldstad, a private practitioner at Midwest Eye Care in Omaha, Neb. But once in a while there is a patient who has noticed vision changes but didn't realize he or she had diabetes until alerted during an eye exam that there were signs of the eye disease that is consistent with the condition, he says.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends eye examinations whenever individuals notice any vision changes or injury. Adults with no symptoms or known risk factors for eye disease should get a base line exam by age 40 and return every two to four years for evaluations until their mid-50s. From 55 to 64, the AAO recommends exams every one to three years, and every one to two years for those 65 and older.

What We’re Not Looking After: Our Eyes

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 20, 2010

Joe Lovett was scared, really scared. Being able to see was critical to his work as a documentary filmmaker and, he thought, to his ability to live independently. But longstanding glaucoma threatened to rob him of this most important sense — the sense that more than 80 percent of Americans worry most about losing, according to a recent survey.

Partly to assuage his fears, partly to learn how to cope if he becomes blind, and partly to alert Americans to the importance of regular eye care, Mr. Lovett, 65, decided to do what he does best. He produced a documentary called “Going Blind,” with the telling subtitle “Coming Out of the Dark About Vision Loss.”

In addition to Mr. Lovett, the film features six people whose vision was destroyed or severely impaired by disease or injury:

¶Jessica Jones, an artist who lost her sight to diabetic retinopathy at age 32, but now teaches art to blind and disabled children.

¶Emmet Teran, a schoolboy whose vision is limited by albinism, a condition he inherited from his father, and who uses comedy to help him cope with bullies.

¶Peter D’Elia, an architect in his 80s who has continued working despite vision lost to age-related macular degeneration.

¶Ray Korman, blinded at age 40 by an incurable eye disease called retinitis pigmentosa, whose life was turned around by a guide dog and who now promotes this aid to others.

¶Patricia Williams, a fiercely independent woman legally blind because of glaucoma and a traumatic injury, who continues to work as a program support assistant for the Veterans Administration.

¶Steve Baskis, a soldier blinded at age 22 by a roadside bomb in Iraq, who now lives independently and offers encouragement to others injured at war.

Sadly, the nationwide survey (conducted Sept. 8 through 12 by Harris Interactive) showed that only a small minority of those most at risk get the yearly eye exams that could detect a vision problem and prevent, delay or even reverse its progression. Fully 86 percent of those who already have an eye disease do not get routine exams, the telephone survey of 1,004 adults revealed.

The survey was commissioned by Lighthouse International, the world-renowned nonprofit organization in New York that seeks to prevent vision loss and treats those affected. In an interview, Lighthouse’s president, Mark G. Ackermann, emphasized that our rapidly aging population predicts a rising prevalence of sight-robbing diseases like age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy that will leave “some 61 million Americans at high risk of serious vision loss.”

The Benefits of a Checkup

Low vision and blindness are costly problems in more ways than you might think. In addition to the occupational and social consequences of vision loss, there are serious medical costs, not the least of them from injuries due to falls. Poor vision accounts for 18 percent of broken hips, Mr. Ackermann said.

So, why, I asked, don’t more of us get regular eye exams? For one thing, they are not covered by Medicare and many health insurers. Even the new health care law has yet to include basic eye exams and rehabilitation services for vision loss, though advocates like Mr. Ackermann are pushing hard for this coverage in regulations now being prepared.

Lighthouse International is one of five regional low-vision centers participating in a Medicare demonstration project in which trained therapists teach patients how to use optical devices, how to make changes in their homes to facilitate independence and how to maintain mobility outside the home. Thus far, an interim analysis showed, the costs of providing these services are well below what had been anticipated.

I can think of no good reason for excluding this coverage in the nation’s health care overhaul, any more than there are good excuses for Medicare’s failure to pay for hearing aids. A lack of coverage for such services will inevitably carry its own heavy costs in the long run.

But even those who have insurance or can pay out of pocket are often reluctant to go for regular eye exams. Fear and depression are common impediments for those at risk of vision loss, said Dr. Bruce Rosenthal, low-vision specialist at Lighthouse. Patients worry that they could become totally blind and unable to work, read or drive a car, he said.

Yet many people fail to realize that early detection can result in vision-preserving therapy. Those at risk include people with diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol or cardiovascular disease, as well as anyone who has been a smoker or has a family history of an eye disorder like macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma.

Smoking raises the risk of macular degeneration two to six times, Dr. Rosenthal said.

Furthermore, he said, the eyes are truly a window to the body, and a proper eye exam can often alert physicians to a serious underlying disease like diabetes, multiple sclerosis or even a brain tumor.

Reasons Not to Wait

He recommends that all children have “a basic professional eye exam” before they start elementary school. “Being able to read the eye chart, which tests distance vision, is not enough, since most learning occurs close up,” he said. “One in three New York City schoolchildren has a vision deficit. Learning and behavior problems can result if a child does not receive adequate vision correction.”

Annual checkups are best done from age 20 on, and certainly by age 40, Dr. Rosenthal said. Waiting until you have symptoms is hardly ideal. For example, glaucoma in its early stages is a silent thief of sight. It could take 10 years to cause a noticeable problem, by which time the changes are irreversible.

For those who already have serious vision loss, the range of visual aids now available is extraordinary — and increasing almost daily. There are large-picture closed-circuit televisions, devices like the Kindle that can read books aloud, computers and readers that scan documents and read them out loud, Braille and large-print music, as well as the more familiar long canes and guide dogs.

On Oct. 13, President Obama signed legislation requiring that every new technological advance be made accessible to people who are blind, visually impaired or deaf.

Producing “Going Blind” helped to reassure Mr. Lovett that he will be able to cope, whatever the future holds. Meanwhile, the regular checkups and treatments he has received have slowed progression of his glaucoma, allowing him to continue his professional work and ride his bicycle along the many new bike paths in New York City.

Just Because One’s Vision Is Waning, Hope Doesn’t Have To

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 27, 2010

Jim Vlock is on a mission. Afflicted 15 years ago with macular degeneration, a retinal disorder that erodes central vision and thus the ability to drive, read, watch television and recognize faces, Mr. Vlock is determined to spread the word about the many devices that can help people like him live more fulfilling, independent and productive lives.

Mr. Vlock, now 84 and a longtime resident of Woodbridge, Conn., told me in an interview that he sought help at three of the country’s best medical centers: Yale, the Cleveland Clinic and Columbia. And though they tried to treat his vision problem, none told him there were ways to improve his life within the limits of his visual loss.

“These institutions attempt to cure, but they are not particularly interested or knowledgeable about providing ways to overcome low vision,” he said.

His wife, Gail Brekke, said: “We had been spending all our time focusing on a possible cure — stem cells, laser treatments, injections — we were willing to go to the ends of the earth. We didn’t want to live in a land of resignation. We thought there must be something out there to help. But like most of medicine, the specialists we consulted were not knowledgeable about helping you live your life without a pill or scalpel.”

Seeking Out Helpful Tools

Spurred by his distress over having to give up reading and television, as well as driving and playing tennis, Mr. Vlock, a retired steel executive who describes himself as “a proactive person,” found what he needed on his own. A technician who teaches people with visual impairment how to use computers suggested he seek help at the Veterans Health Administration’s medical center in West Haven, Conn., where he was entitled to free care as a Navy veteran of World War II.

With Mr. Vlock, I visited this full-service center, where he said he underwent “the longest and most comprehensive evaluation” he’d yet received — a full six hours of testing — along with a plethora of visual aid devices, including six pairs of specialized glasses for different tasks, a talking watch and a magnified travel mirror to help him shave.

Most important, he learned to use a computer with an enlarged keyboard and magnified screen for reading text and e-mail; if he can’t make out what’s on the screen, it will read to him out loud. (He has since donated three of these computers to the public library and local residences for the elderly.)

Now Mr. Vlock can again read and enjoy television, theater, ballgames and e-mail. Not only did the V.A. provide the tools to make this possible; it also gave him the instruction and training he needed to function well at home and at work, where he is a consultant to Fox Steel, the Connecticut company he previously owned.

He learned of still other services through a chance meeting with David Lepofsky, a lawyer in Toronto who has been blind since he was a teenager yet completed law school and a master’s degree at Harvard. In a long e-mail to Ms. Brekke, Mr. Lepofsky wrote, “There is no reason why, despite his vision limitations, Jim should not be able to read what he wants, including daily newspapers, in a relaxing way and without having to become a high-end computer scientist.”

With Mr. Lepofsky’s guidance, Mr. Vlock acquired a Victor Reader Stream, a device that downloads and plays all manner of audio books. He gained access to the National Federation of the Blind’s newsline; using his telephone touch pad, he can listen to articles from newspapers throughout the country as early as 8 a.m. each day.

“This was a transformative experience,” he said. “I’m now able to do all these things.”

The V.A. rehabilitation programs are meant to help blind and low-vision veterans and active service members regain their independence and quality of life and to function as full members of their families and communities.

Lisa-Anne Mowerson, acting chief of the agency’s Eastern Blind Rehabilitation Center in West Haven, calls the center “the best-kept secret.”

“It’s hard for people to find us,” Ms. Mowerson told me. “A person’s vision problem doesn’t have to be service-connected for them to receive care here. Their vision problem could be due to diabetes or glaucoma” — or, as in Mr. Vlock’s case, macular degeneration, a familial condition that had afflicted his father and two uncles.

There are 10 advanced-care vision centers for veterans around the country. The center Ms. Mowerson runs serves the entire Eastern Seaboard, with referrals from 13 veterans’ centers that provide more basic low-vision services.

“We don’t just give devices, we give training inpatient and out, at home and at work,” Ms. Mowerson said. “We may spend 20 hours with individuals to make sure they know how to use the devices properly and can cope independently, which takes training and practice. These devices are available in the community, but people are not trained how to use them.”

Mr. Vlock said, “There’s a dedication here — you don’t feel like you’re inconveniencing anyone.”

Insurance Stops Short

For nonveterans with visual impairments, more is lacking than just adequate training. Also absent is insurance coverage.

As with hearing aids, neither Medicare nor private insurance covers these tools and services, a failure of our penny-wise and pound-foolish medical care system that often ends up costing society far more in lost wages and personal care.

“The private sector has to step up,” said Kara Gagnon, director of low-vision optometry at the V.A. in West Haven. “Success is directly tied to the quality of the exam and the training — two hours doesn’t do it.

“We teach patients where their sweet spot is — the part of their remaining vision through which they can see best — and how to access it so they can see faces and read fluently. Too often we get patients who’ve been unable to read for 20 years, who’ve lost their jobs, their wives, their homes.

“Our philosophy is to get patients to do things for themselves, including cooking and laundry, so they can cycle out of depression and feel fulfilled. We ask about their goals, what they enjoyed doing before they became visually impaired. I can get them back to everything except driving a car and flying a plane.”

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 20, 2010

Joe Lovett was scared, really scared. Being able to see was critical to his work as a documentary filmmaker and, he thought, to his ability to live independently. But longstanding glaucoma threatened to rob him of this most important sense — the sense that more than 80 percent of Americans worry most about losing, according to a recent survey.

Partly to assuage his fears, partly to learn how to cope if he becomes blind, and partly to alert Americans to the importance of regular eye care, Mr. Lovett, 65, decided to do what he does best. He produced a documentary called “Going Blind,” with the telling subtitle “Coming Out of the Dark About Vision Loss.”

In addition to Mr. Lovett, the film features six people whose vision was destroyed or severely impaired by disease or injury:

¶Jessica Jones, an artist who lost her sight to diabetic retinopathy at age 32, but now teaches art to blind and disabled children.

¶Emmet Teran, a schoolboy whose vision is limited by albinism, a condition he inherited from his father, and who uses comedy to help him cope with bullies.

¶Peter D’Elia, an architect in his 80s who has continued working despite vision lost to age-related macular degeneration.

¶Ray Korman, blinded at age 40 by an incurable eye disease called retinitis pigmentosa, whose life was turned around by a guide dog and who now promotes this aid to others.

¶Patricia Williams, a fiercely independent woman legally blind because of glaucoma and a traumatic injury, who continues to work as a program support assistant for the Veterans Administration.

¶Steve Baskis, a soldier blinded at age 22 by a roadside bomb in Iraq, who now lives independently and offers encouragement to others injured at war.

Sadly, the nationwide survey (conducted Sept. 8 through 12 by Harris Interactive) showed that only a small minority of those most at risk get the yearly eye exams that could detect a vision problem and prevent, delay or even reverse its progression. Fully 86 percent of those who already have an eye disease do not get routine exams, the telephone survey of 1,004 adults revealed.

The survey was commissioned by Lighthouse International, the world-renowned nonprofit organization in New York that seeks to prevent vision loss and treats those affected. In an interview, Lighthouse’s president, Mark G. Ackermann, emphasized that our rapidly aging population predicts a rising prevalence of sight-robbing diseases like age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy that will leave “some 61 million Americans at high risk of serious vision loss.”

The Benefits of a Checkup

Low vision and blindness are costly problems in more ways than you might think. In addition to the occupational and social consequences of vision loss, there are serious medical costs, not the least of them from injuries due to falls. Poor vision accounts for 18 percent of broken hips, Mr. Ackermann said.

So, why, I asked, don’t more of us get regular eye exams? For one thing, they are not covered by Medicare and many health insurers. Even the new health care law has yet to include basic eye exams and rehabilitation services for vision loss, though advocates like Mr. Ackermann are pushing hard for this coverage in regulations now being prepared.

Lighthouse International is one of five regional low-vision centers participating in a Medicare demonstration project in which trained therapists teach patients how to use optical devices, how to make changes in their homes to facilitate independence and how to maintain mobility outside the home. Thus far, an interim analysis showed, the costs of providing these services are well below what had been anticipated.

I can think of no good reason for excluding this coverage in the nation’s health care overhaul, any more than there are good excuses for Medicare’s failure to pay for hearing aids. A lack of coverage for such services will inevitably carry its own heavy costs in the long run.

But even those who have insurance or can pay out of pocket are often reluctant to go for regular eye exams. Fear and depression are common impediments for those at risk of vision loss, said Dr. Bruce Rosenthal, low-vision specialist at Lighthouse. Patients worry that they could become totally blind and unable to work, read or drive a car, he said.

Yet many people fail to realize that early detection can result in vision-preserving therapy. Those at risk include people with diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol or cardiovascular disease, as well as anyone who has been a smoker or has a family history of an eye disorder like macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma.

Smoking raises the risk of macular degeneration two to six times, Dr. Rosenthal said.

Furthermore, he said, the eyes are truly a window to the body, and a proper eye exam can often alert physicians to a serious underlying disease like diabetes, multiple sclerosis or even a brain tumor.

Reasons Not to Wait

He recommends that all children have “a basic professional eye exam” before they start elementary school. “Being able to read the eye chart, which tests distance vision, is not enough, since most learning occurs close up,” he said. “One in three New York City schoolchildren has a vision deficit. Learning and behavior problems can result if a child does not receive adequate vision correction.”

Annual checkups are best done from age 20 on, and certainly by age 40, Dr. Rosenthal said. Waiting until you have symptoms is hardly ideal. For example, glaucoma in its early stages is a silent thief of sight. It could take 10 years to cause a noticeable problem, by which time the changes are irreversible.

For those who already have serious vision loss, the range of visual aids now available is extraordinary — and increasing almost daily. There are large-picture closed-circuit televisions, devices like the Kindle that can read books aloud, computers and readers that scan documents and read them out loud, Braille and large-print music, as well as the more familiar long canes and guide dogs.

On Oct. 13, President Obama signed legislation requiring that every new technological advance be made accessible to people who are blind, visually impaired or deaf.

Producing “Going Blind” helped to reassure Mr. Lovett that he will be able to cope, whatever the future holds. Meanwhile, the regular checkups and treatments he has received have slowed progression of his glaucoma, allowing him to continue his professional work and ride his bicycle along the many new bike paths in New York City.

Just Because One’s Vision Is Waning, Hope Doesn’t Have To

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times : December 27, 2010

Jim Vlock is on a mission. Afflicted 15 years ago with macular degeneration, a retinal disorder that erodes central vision and thus the ability to drive, read, watch television and recognize faces, Mr. Vlock is determined to spread the word about the many devices that can help people like him live more fulfilling, independent and productive lives.

Mr. Vlock, now 84 and a longtime resident of Woodbridge, Conn., told me in an interview that he sought help at three of the country’s best medical centers: Yale, the Cleveland Clinic and Columbia. And though they tried to treat his vision problem, none told him there were ways to improve his life within the limits of his visual loss.

“These institutions attempt to cure, but they are not particularly interested or knowledgeable about providing ways to overcome low vision,” he said.

His wife, Gail Brekke, said: “We had been spending all our time focusing on a possible cure — stem cells, laser treatments, injections — we were willing to go to the ends of the earth. We didn’t want to live in a land of resignation. We thought there must be something out there to help. But like most of medicine, the specialists we consulted were not knowledgeable about helping you live your life without a pill or scalpel.”

Seeking Out Helpful Tools

Spurred by his distress over having to give up reading and television, as well as driving and playing tennis, Mr. Vlock, a retired steel executive who describes himself as “a proactive person,” found what he needed on his own. A technician who teaches people with visual impairment how to use computers suggested he seek help at the Veterans Health Administration’s medical center in West Haven, Conn., where he was entitled to free care as a Navy veteran of World War II.

With Mr. Vlock, I visited this full-service center, where he said he underwent “the longest and most comprehensive evaluation” he’d yet received — a full six hours of testing — along with a plethora of visual aid devices, including six pairs of specialized glasses for different tasks, a talking watch and a magnified travel mirror to help him shave.

Most important, he learned to use a computer with an enlarged keyboard and magnified screen for reading text and e-mail; if he can’t make out what’s on the screen, it will read to him out loud. (He has since donated three of these computers to the public library and local residences for the elderly.)

Now Mr. Vlock can again read and enjoy television, theater, ballgames and e-mail. Not only did the V.A. provide the tools to make this possible; it also gave him the instruction and training he needed to function well at home and at work, where he is a consultant to Fox Steel, the Connecticut company he previously owned.

He learned of still other services through a chance meeting with David Lepofsky, a lawyer in Toronto who has been blind since he was a teenager yet completed law school and a master’s degree at Harvard. In a long e-mail to Ms. Brekke, Mr. Lepofsky wrote, “There is no reason why, despite his vision limitations, Jim should not be able to read what he wants, including daily newspapers, in a relaxing way and without having to become a high-end computer scientist.”

With Mr. Lepofsky’s guidance, Mr. Vlock acquired a Victor Reader Stream, a device that downloads and plays all manner of audio books. He gained access to the National Federation of the Blind’s newsline; using his telephone touch pad, he can listen to articles from newspapers throughout the country as early as 8 a.m. each day.

“This was a transformative experience,” he said. “I’m now able to do all these things.”

The V.A. rehabilitation programs are meant to help blind and low-vision veterans and active service members regain their independence and quality of life and to function as full members of their families and communities.

Lisa-Anne Mowerson, acting chief of the agency’s Eastern Blind Rehabilitation Center in West Haven, calls the center “the best-kept secret.”

“It’s hard for people to find us,” Ms. Mowerson told me. “A person’s vision problem doesn’t have to be service-connected for them to receive care here. Their vision problem could be due to diabetes or glaucoma” — or, as in Mr. Vlock’s case, macular degeneration, a familial condition that had afflicted his father and two uncles.

There are 10 advanced-care vision centers for veterans around the country. The center Ms. Mowerson runs serves the entire Eastern Seaboard, with referrals from 13 veterans’ centers that provide more basic low-vision services.

“We don’t just give devices, we give training inpatient and out, at home and at work,” Ms. Mowerson said. “We may spend 20 hours with individuals to make sure they know how to use the devices properly and can cope independently, which takes training and practice. These devices are available in the community, but people are not trained how to use them.”

Mr. Vlock said, “There’s a dedication here — you don’t feel like you’re inconveniencing anyone.”

Insurance Stops Short

For nonveterans with visual impairments, more is lacking than just adequate training. Also absent is insurance coverage.

As with hearing aids, neither Medicare nor private insurance covers these tools and services, a failure of our penny-wise and pound-foolish medical care system that often ends up costing society far more in lost wages and personal care.

“The private sector has to step up,” said Kara Gagnon, director of low-vision optometry at the V.A. in West Haven. “Success is directly tied to the quality of the exam and the training — two hours doesn’t do it.

“We teach patients where their sweet spot is — the part of their remaining vision through which they can see best — and how to access it so they can see faces and read fluently. Too often we get patients who’ve been unable to read for 20 years, who’ve lost their jobs, their wives, their homes.

“Our philosophy is to get patients to do things for themselves, including cooking and laundry, so they can cycle out of depression and feel fulfilled. We ask about their goals, what they enjoyed doing before they became visually impaired. I can get them back to everything except driving a car and flying a plane.”

Let the Sunshine in, but Not the Harmful Rays

By Lesley Alderman : NY Times : January 14, 2011

Sunglasses are not just for summer.

Skiing on fresh snow, skating on reflective ice or hiking at high altitudes can be harder on your eyes than a day at the beach. Snow, as many East Coast readers may have noticed this week, reflects nearly 80 percent of the sun’s rays. Dry beach sand? Just 15 percent.

Most of us already know that ultraviolet (UV) rays can cause skin cancer and other problems. But that’s not all there is to worry about. “Most people don’t appreciate the damage that UV rays can do to their eyes,” said Dr. Rachel J. Bishop, a clinical ophthalmologist at the National Eye Institute in Bethesda, Md.

Winter or summer, hours of bright sunlight can burn the surface of the eye, causing a temporary and painful condition known as photokeratitis. Over time, unprotected exposure can contribute to cataracts, as well as cancer of the eyelids and the skin around the eyes.

UV exposure also may increase the risk of macular degeneration, the leading cause of blindness in people over age 65. While cataracts can be removed surgically, there is no way to reverse damage to the macula, the area in the center of the retina.

Worried? Consider this article license to buy yourself a new pair of UV-protective shades. But don’t let price and style be your only guides.

“Some cheap sunglasses are great, some expensive ones are not,” said Dr. Lee R. Duffner, an ophthalmologist in Hollywood, Fla., and a clinical correspondent for the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

In fact, some knockoff designer frames may do your eyes more harm than if you’d worn no glasses at all.

Below, some advice on how to find sunglasses that will protect your eyes without plundering your wallet.

READ THE FINE PRINT

Prolonged exposure to UV radiation damages the surface tissues of the eye as well as the retina and the lens. Yet while the Food and Drug Administration regulates sunglasses as medical devices, the agency does not stipulate that they must provide any particular level of UV protection. The wares at the average sunglasses store therefore can range from protective to wholly ineffective.

Look for labels and tags indicating that a pair of sunglasses provides at least “98 percent UV protection” or that it “blocks 98 percent of UVA and UVB rays.” If there is no label, or it says something vague like “UV absorbing” or “blocks most UV light,” don’t buy them — the sunglasses may not offer much protection.

For the best defense, look for sunglasses that “block all UV radiation up to 400 nanometers,” which is equivalent to blocking 100 percent of UV rays, advised Dr. Duffner.

CHOOSE THE RIGHT STYLE

Ideally, your sunglasses should cover the sides of your eyes to prevent stray light from entering. Wraparound lenses are best, but if that’s not an appealing style, look for close-fitting glasses with wide lenses. Avoid models with small lenses, such as John Lennon-style sunglasses.

Don’t be seduced by dark tints. UV protection is not related to how dark the lens is. Sunglasses tinted green, amber, red and gray may offer the same protection as dark lenses. For the least color distortion, pick gray lenses, said Dr. Duffner.

If you are frequently distracted by glare while driving, boating or skiing, look for polarized lenses, which block the horizontal light waves that create glare. But remember, polarization in itself will not block UV light. Make sure the lenses also offer 98 percent or 100 percent UV protection.

Though the F.D.A. does not require that sunglasses have UV protection, the agency does insist that they meet impact-resistance standards — which basically means they won’t shatter when struck. Even so, if you wear sunglasses while cycling, sailing or gardening, for instance, consider purchasing a pair with polycarbonate lenses, which are 10 times more durable than regular plastic or glass lenses.

AVOID SIDEWALK VENDORS

Buy a pair of chic Chanel knockoffs that offer no UV protection, and you might look swell — but your eyes will suffer. The tinted lenses will relax your pupils, letting more damaging radiation hit your retina than if you were wearing no glasses at all.

To play it safe, buy glasses from well-established drug, chain or department stores, rather than from vendors on the street. Shop around: you should be able to find a pair of drugstore sunglasses for $10 to $20 that provide all the protection you need.

DON’T FORGET THE CHILDREN

Upgrade your children from their Dora and Spider-man toy sunglasses to legitimate shades that offer 98 percent to 100 percent UV protection. Children with light-colored eyes are especially vulnerable to sun damage, said Dr. Duffner. The injury is cumulative, so the earlier children get in the habit of wearing shades, the better off their eyes will be.

If your child plays sports regularly, consider also purchasing sport-specific goggles. Eye injuries are the leading cause of blindness in children, and most of those injuries occur when they are playing basketball, baseball, ice hockey or racket sports.

The National Eye Institute says it believes that protective eyewear could prevent 90 percent of sports-related eye injuries in children.

TEST THOSE OLD GLASSES

Reluctant to pop for a new pair of sunglasses? If you already have a favorite pair but don’t know what kind of protection they offer, ask your local eyewear store if they have a UV meter. This device can measure the UV protection of your glasses and help you determine whether you should buy a new pair. “Most opticians have such a meter and can do this very easily,” said Dr. Duffner.

Even if you wear contact lenses that offer UV protection, you’re not in the clear. Contact lenses sit on the cornea in the center of your eyes and so can’t protect the surrounding white area (the conjunctiva) and skin.

“I see many older patients who have growths on the whites of their eyes that were caused by sun damage,” Dr. Bishop said. These yellow bumps, called pinguecula, often lead to eye irritation and dryness and may eventually disrupt vision. To prevent them, adults with contact lenses still must wear sunglasses outdoors.

Lastly, if you wear prescription glasses, you can avoid buying sunglasses by either purchasing clip-ons that attach to your frames or having a UV coating applied to your lenses. Presto, you’ll have two pairs in one.

What to Do When You Can’t Read the Fine Print

By Michelle Andrews : NY Times : April 1, 2011

Everything seems to stiffen up as people age, and our eyes are no exception. As the years go by, the lens of the eye becomes harder and less elastic. The result is a gradual worsening of the ability to focus on objects up close, called presbyopia.

There’s no escaping it. Diet and exercise, the baby boomers’ weapons of choice for warding off age-related health problems, have no effect. Presbyopia generally starts in the mid-40s, when people begin to notice that they have difficulty punching out a number on their mobile phone or reading a book. Over the next 20 years or so, the eyes continue to lose their ability to zoom in on things; by about age 65, it’s often impossible.

“It’s like having a camera with no multifocal option,” said Dr. Rachel J. Bishop, chief of the consult services section of the National Eye Institute.

About four years ago, Freda Dallas noticed that she was having trouble reading and helping her son with his homework. Ms. Dallas, 51, works as a vision therapist with children to correct crossed eyes and other problems at the Ohio State University College of Optometry in Columbus, Ohio.

She knew right away what her problem was. “I was in denial,” she said.

Until then, Ms. Dallas generally wore regular contact lenses to correct her severe myopia, or nearsightedness. She knew that she did not want to switch to glasses with bifocal lenses. Once, during a Jazzercise class, her glasses had flown off and she could not find them without her classmates’ help. She needed an option that would stay put.

Her optometrist suggested multifocal contact lenses, which correct for both distance and near vision problems. Ms. Dallas tried them, and loved them. They’re more expensive than regular contacts or bifocal glasses because she has to replace them every two weeks at an out-of-pocket cost of about $200 annually, including cleaning solution. (Her vision insurance covers another $250 of the cost.)

But it’s worth it. “They’re really comfortable, and I’m sold on them,” she said.

Like many people, when Ms. Dallas first noticed she was having trouble reading she tried to compensate by shining a brighter light on the page. Others try holding reading material at arm’s length. But at some point, even the longest-armed person can no longer read the fine print on a menu.

That’s when it is time to find some help. Both optometrists and ophthalmologists can perform eye exams and prescribe eyeglasses and contact lenses. Ophthalmologists are medical doctors who can also perform eye surgery, like Lasik, to correct refractive errors.

Here’s some advice on what to ask them about, and how to pay for it.

A VISION PLAN

Many employers offer or provide vision insurance for their employees, but it can also be purchased as a stand-alone product. At Vision Service Plan, a large vision insurer, individual coverage costs between $149 and $181 annually, depending on the state, said Gary Brooks, V.S.P.’s president for vision care.

A typical plan covers a comprehensive annual eye exam and provides a certain amount, often a few hundred dollars, toward the purchase of contact lenses or glasses. Like health insurance, prices may be cheaper if members use a practitioner in the insurer’s network.

For many types of corrective lenses, however, vision insurance coverage is inadequate, experts agree. The biggest advantage may be that the coverage encourages baby boomers to get annual eye exams, which can catch vision problems at an early stage.

Glaucoma, for example, damages the optic nerve and is the leading cause of irreversible blindness, yet half of people with glaucoma don’t know it, said Dr. J. Alberto Martinez, an ophthalmologist in private practice in Bethesda, Md.

GLASSES

The easiest and cheapest solution for presbyopia is to go to your local drug or discount store and buy a pair of $10 reading glasses. For those whose only vision problem is presbyopia, cheap reading glasses may do the trick.

But for many patients, one-size-fits-all reading glasses cause eye fatigue, said Dr. Martinez. If that is the case, prescription glasses or contacts may be best.

The least expensive prescription option is bifocal or trifocal glasses with a visible line separating the top portion of the lens, which corrects for distance if necessary, from the bottom portion, which corrects for presbyopia. On trifocals, there is a middle section that corrects for intermediate distances. These lenses can be bought for under $200; frames are priced separately and can run from under $100 to more than $1,000 for those by high-end designers.

Progressive eyeglass lenses — in which the lens power gradually increases from the top of the lens to the bottom — eliminate the unsightly focal lines and avoid the image jump that can occur with traditional lenses. The downside is that progressive lenses often are significantly more expensive than bifocals or trifocals, sometimes $400 or more, and can cause visual distortions that some people have difficulty adjusting to.

CONTACT LENSES

Bifocal and multifocal contact lenses have two or more prescriptions in the same lens, similar to eyeglasses. They come in a range of hard and soft materials with various disposable options.

In the past, some doctors told patients with presbyopia that they were not good candidates for multifocal lenses. Although fitting presbyopic patients with multifocal contacts is more complicated than fitting people without it, it’s a good option for many, said Kathryn Richdale, a senior research associate also at the Ohio State College of Optometry. “The lenses have come a long way in the past few years,” she said.

Expect to pay a fitting fee of up to $200, and up to $500 a year for lenses.

Some patients do well with a different therapeutic approach called monovision. Rather than correcting both eyes for both distance and near vision problems, monovision corrects one eye for distance vision and one eye for near vision. “Your brain learns to ignore the image that’s not in focus,” said Dr. James Salz, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Southern California.

This can be accomplished with contact lenses or through Lasik surgery, which reshapes the cornea. If someone is considering an irreversible process like Lasik, however, it’s important to test monovision first with contact lenses, say experts. And insurance generally does not cover Lasik surgery, which typically costs up to $2,500 per eye.

Research shows that about 70 percent of patients tolerate monovision, said Barry Weissman, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles. As people age and their presbyopia worsens, however, the growing difference between the two corrections often causes discomfort, he added.

LENS REPLACEMENT

As the eye ages, the lens may develop cataracts, or cloudiness. Eye surgeons correct the problem by replacing the lens. Now some of these intraocular lenses can also correct for presbyopia.

But be warned: health insurance will generally cover cataract surgery, but if you opt for one of the new lenses that correct presbyopia rather the standard single-focus lens, you’ll have to pay the difference — up to $2,500 an eye.

Some ophthalmologists are now replacing people’s healthy lenses with presbyopia-correcting lenses. Because it is not medically necessary, insurance won’t cover the $3,000 to $7,000 cost per eye.

And some doctors are wary of the practice. “To correct just for presbyopia, I myself wouldn’t do that,” said Dr. Bishop. “I don’t believe the risks are outweighed by the benefits.”

By Michelle Andrews : NY Times : April 1, 2011

Everything seems to stiffen up as people age, and our eyes are no exception. As the years go by, the lens of the eye becomes harder and less elastic. The result is a gradual worsening of the ability to focus on objects up close, called presbyopia.

There’s no escaping it. Diet and exercise, the baby boomers’ weapons of choice for warding off age-related health problems, have no effect. Presbyopia generally starts in the mid-40s, when people begin to notice that they have difficulty punching out a number on their mobile phone or reading a book. Over the next 20 years or so, the eyes continue to lose their ability to zoom in on things; by about age 65, it’s often impossible.

“It’s like having a camera with no multifocal option,” said Dr. Rachel J. Bishop, chief of the consult services section of the National Eye Institute.

About four years ago, Freda Dallas noticed that she was having trouble reading and helping her son with his homework. Ms. Dallas, 51, works as a vision therapist with children to correct crossed eyes and other problems at the Ohio State University College of Optometry in Columbus, Ohio.

She knew right away what her problem was. “I was in denial,” she said.

Until then, Ms. Dallas generally wore regular contact lenses to correct her severe myopia, or nearsightedness. She knew that she did not want to switch to glasses with bifocal lenses. Once, during a Jazzercise class, her glasses had flown off and she could not find them without her classmates’ help. She needed an option that would stay put.

Her optometrist suggested multifocal contact lenses, which correct for both distance and near vision problems. Ms. Dallas tried them, and loved them. They’re more expensive than regular contacts or bifocal glasses because she has to replace them every two weeks at an out-of-pocket cost of about $200 annually, including cleaning solution. (Her vision insurance covers another $250 of the cost.)

But it’s worth it. “They’re really comfortable, and I’m sold on them,” she said.

Like many people, when Ms. Dallas first noticed she was having trouble reading she tried to compensate by shining a brighter light on the page. Others try holding reading material at arm’s length. But at some point, even the longest-armed person can no longer read the fine print on a menu.

That’s when it is time to find some help. Both optometrists and ophthalmologists can perform eye exams and prescribe eyeglasses and contact lenses. Ophthalmologists are medical doctors who can also perform eye surgery, like Lasik, to correct refractive errors.

Here’s some advice on what to ask them about, and how to pay for it.

A VISION PLAN

Many employers offer or provide vision insurance for their employees, but it can also be purchased as a stand-alone product. At Vision Service Plan, a large vision insurer, individual coverage costs between $149 and $181 annually, depending on the state, said Gary Brooks, V.S.P.’s president for vision care.

A typical plan covers a comprehensive annual eye exam and provides a certain amount, often a few hundred dollars, toward the purchase of contact lenses or glasses. Like health insurance, prices may be cheaper if members use a practitioner in the insurer’s network.

For many types of corrective lenses, however, vision insurance coverage is inadequate, experts agree. The biggest advantage may be that the coverage encourages baby boomers to get annual eye exams, which can catch vision problems at an early stage.

Glaucoma, for example, damages the optic nerve and is the leading cause of irreversible blindness, yet half of people with glaucoma don’t know it, said Dr. J. Alberto Martinez, an ophthalmologist in private practice in Bethesda, Md.

GLASSES

The easiest and cheapest solution for presbyopia is to go to your local drug or discount store and buy a pair of $10 reading glasses. For those whose only vision problem is presbyopia, cheap reading glasses may do the trick.

But for many patients, one-size-fits-all reading glasses cause eye fatigue, said Dr. Martinez. If that is the case, prescription glasses or contacts may be best.

The least expensive prescription option is bifocal or trifocal glasses with a visible line separating the top portion of the lens, which corrects for distance if necessary, from the bottom portion, which corrects for presbyopia. On trifocals, there is a middle section that corrects for intermediate distances. These lenses can be bought for under $200; frames are priced separately and can run from under $100 to more than $1,000 for those by high-end designers.

Progressive eyeglass lenses — in which the lens power gradually increases from the top of the lens to the bottom — eliminate the unsightly focal lines and avoid the image jump that can occur with traditional lenses. The downside is that progressive lenses often are significantly more expensive than bifocals or trifocals, sometimes $400 or more, and can cause visual distortions that some people have difficulty adjusting to.

CONTACT LENSES

Bifocal and multifocal contact lenses have two or more prescriptions in the same lens, similar to eyeglasses. They come in a range of hard and soft materials with various disposable options.

In the past, some doctors told patients with presbyopia that they were not good candidates for multifocal lenses. Although fitting presbyopic patients with multifocal contacts is more complicated than fitting people without it, it’s a good option for many, said Kathryn Richdale, a senior research associate also at the Ohio State College of Optometry. “The lenses have come a long way in the past few years,” she said.

Expect to pay a fitting fee of up to $200, and up to $500 a year for lenses.

Some patients do well with a different therapeutic approach called monovision. Rather than correcting both eyes for both distance and near vision problems, monovision corrects one eye for distance vision and one eye for near vision. “Your brain learns to ignore the image that’s not in focus,” said Dr. James Salz, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Southern California.

This can be accomplished with contact lenses or through Lasik surgery, which reshapes the cornea. If someone is considering an irreversible process like Lasik, however, it’s important to test monovision first with contact lenses, say experts. And insurance generally does not cover Lasik surgery, which typically costs up to $2,500 per eye.

Research shows that about 70 percent of patients tolerate monovision, said Barry Weissman, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles. As people age and their presbyopia worsens, however, the growing difference between the two corrections often causes discomfort, he added.

LENS REPLACEMENT

As the eye ages, the lens may develop cataracts, or cloudiness. Eye surgeons correct the problem by replacing the lens. Now some of these intraocular lenses can also correct for presbyopia.

But be warned: health insurance will generally cover cataract surgery, but if you opt for one of the new lenses that correct presbyopia rather the standard single-focus lens, you’ll have to pay the difference — up to $2,500 an eye.

Some ophthalmologists are now replacing people’s healthy lenses with presbyopia-correcting lenses. Because it is not medically necessary, insurance won’t cover the $3,000 to $7,000 cost per eye.

And some doctors are wary of the practice. “To correct just for presbyopia, I myself wouldn’t do that,” said Dr. Bishop. “I don’t believe the risks are outweighed by the benefits.”

Act Fast to Save Sight if Signs of Danger to the Retina Appear

By Jane E. Brody : NY Times November 7, 2011

The eyes may be windows to the soul, but the retina is the brain’s window to the world. When the retina is injured, vision is seriously threatened and may be lost entirely if the problem is not quickly addressed.

The retina is a layer of tissue at the back of the eye that collects light relayed through the lens. Special photoreceptor cells in the retina convert light into nerve impulses, which are transmitted to the brain. At the retina’s center is an especially critical area called the macula, which enables you to see anything directly in front of you, like words on a page, a person’s face, the road ahead or the image on a screen.

When blood flow through the retina is blocked or when the retina pulls away from the wall of the eye, getting the problem properly diagnosed can be an emergency. Modern treatments can do wonders if they are begun before the damage is irreversible. But a delay in getting to a retinal specialist can diminish the ability of even the best therapy to preserve or restore normal vision.

As with all living tissue, the retina is highly dependent on a constant supply of oxygen-carrying blood. Should anything disrupt that, vision is at risk. Two retinal mishaps, retinal-vein occlusion and retinal detachment, can occur at any age, but both are more common among older people.

Recognizing a Blockage